by Shawn Burke, Ph.D.

Introduction

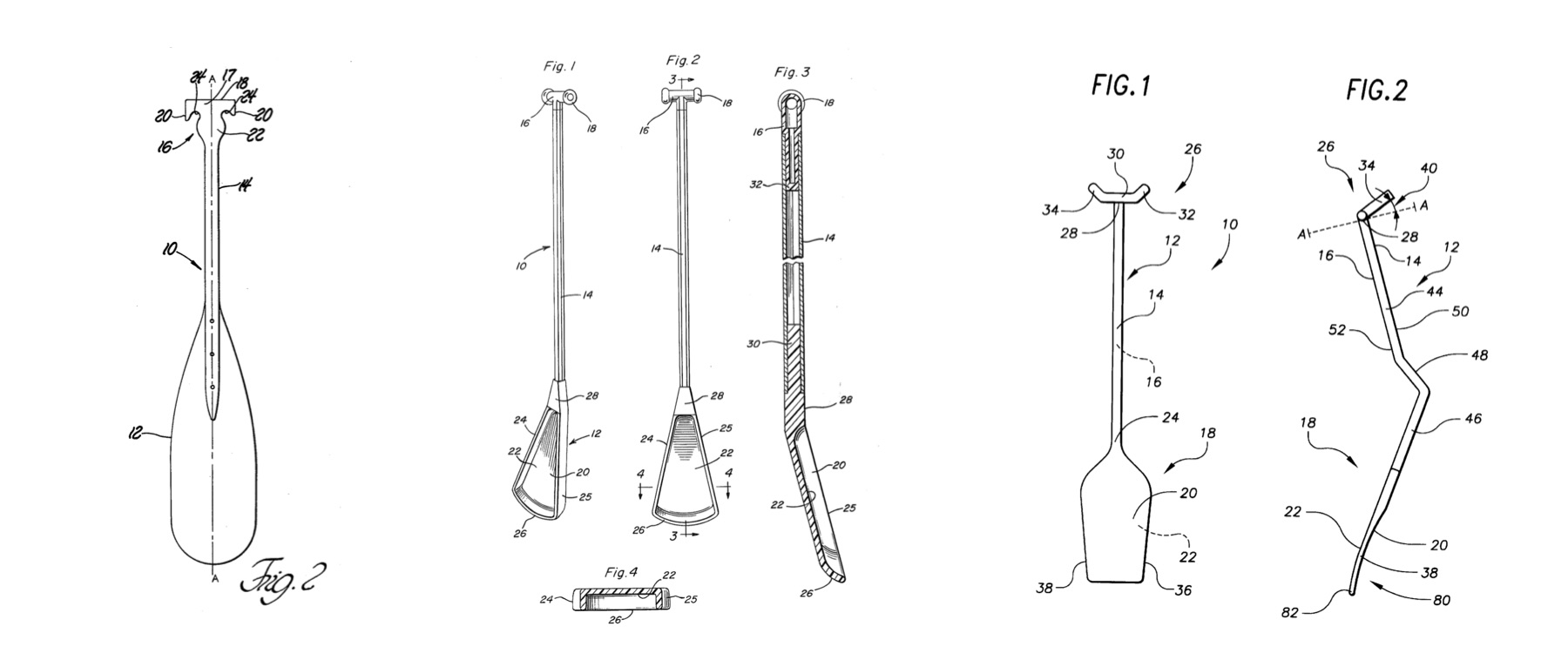

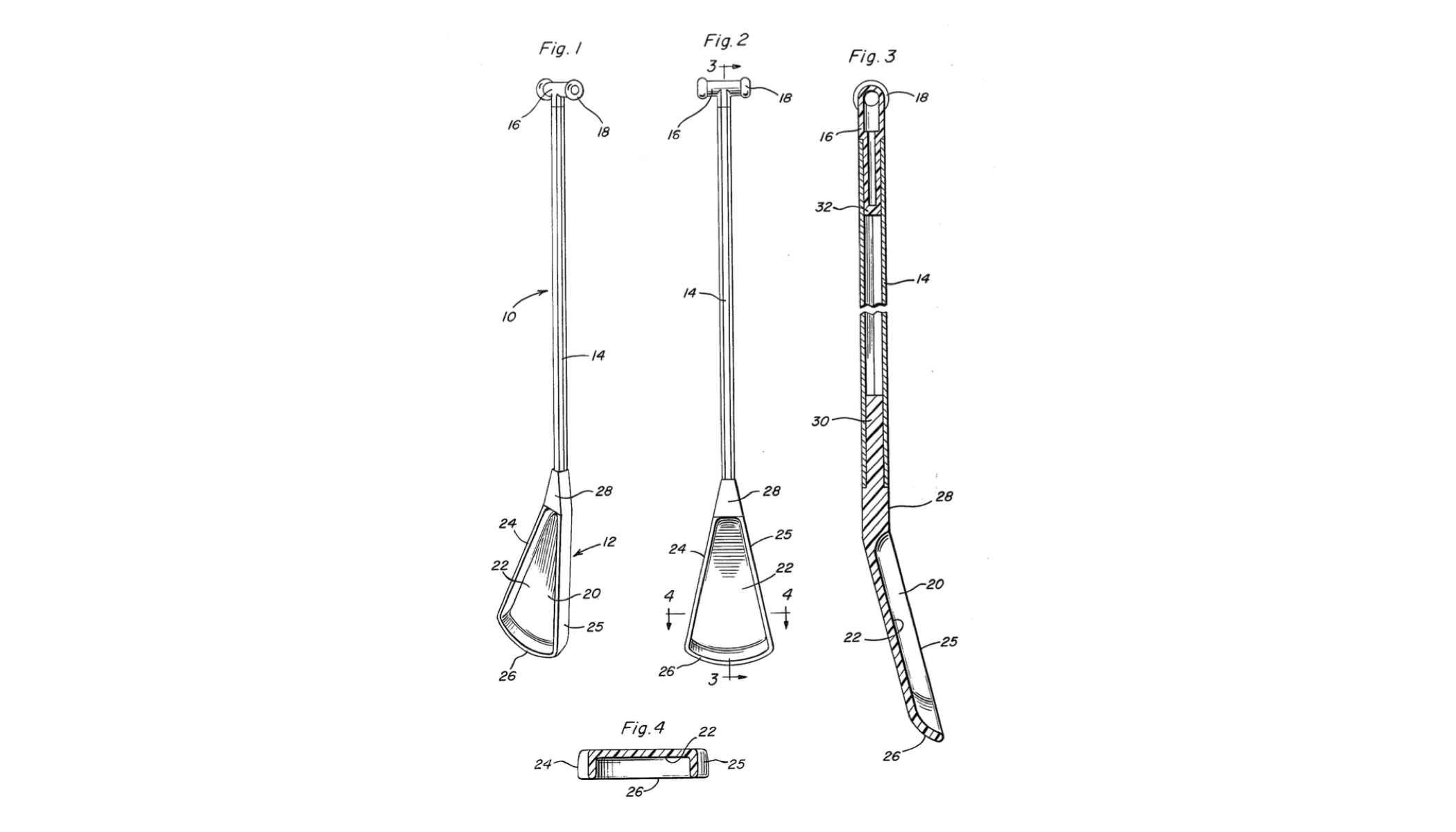

The other day I was searching for patents contemporaneous with Gene Jensen’s bentshaft paddle innovation.[1] Along the way my attention was diverted by a list of curious inventions. Each was a novel paddle or paddling mechanism; all of them looked odd. While I understand the motivation behind each, I have never seen a commercial version of any. In fact, two of them struck me as being a bit impractical. I’ve included a few figures from these patents – United States patents 4,133,285, 4,303,402, and 6,042,438[2] – as examples in Fig. 1. We’ll return to these patents in more detail below.

Figure 1: Figures from a few paddle patents.

As an engineer and inventor, I identified with these inventors’ plight. We see something that needs improvement. We have an idea – or more likely a whole slew of ideas – of how to address this need. Through prototyping, experiment, thought experiment and the like we sieve through these ideas until (hopefully) one of them survives the ordeal, and sticks. It’s less of an “Aha!” moment and more of a slog. We convince ourselves that we’ve invented the proverbial better mousetrap. And for one reason or another we submit a patent application on our invention to the U.S. Patent Office.[3]

Then we wait. Eventually we hear back from the patent examiner assigned to our application. More likely than not they rejected our patent application – completely rejected it. Wait; what do you mean that my idea wasn’t original? Whereupon we engage in a back-and-forth with the examiner, via mail, through our patent counsel.[4] We explain how our idea is different than prior art identified by the examiner. They point out why it isn’t. And over time, if we’re successful, we meet somewhere in the middle. Whereupon we’re issued a legal document: our patent. While our patent is narrower in scope than we originally expected (or certainly hoped), it’s ours. The question becomes, what do we do with it? Which quickly morphs into, who cares about what we’ve invented?

Good patents – and by that, I mean ones that are clearly written, logically organized, don’t invent new lexicography to describe the invention, and protect the disclosed invention – are enjoyable to read. They’re a bit like a mystery: here’s a problem; how do we fix it? Whereupon the solution unfolds before our eyes, hopefully in new and unexpected ways. Sort of like reading Andy Weir’s The Martian, minus the drama (and Mars).

Now we could dive right in and explore the patents listed above. But since many if not most of you will be unfamiliar with patents’ unique style conventions, we’ll first review what patents are, and how they’re organized. This should help you zero in on the relevant bits and how they relate to each other.

Disclaimer

Please note that I’m neither a patent attorney nor a patent agent. I’m an engineer. (Please read those last two sentences one more time.) What follows is how this engineer understands the legal framework underlying patents. If you want the definitive word on patent law, please seek out a patent attorney. The legal landscape of patents is constantly evolving and it’s their job to master it. If you’re seeing patent advice, please seek out a patent attorney or patent agent. I can recommend a few.

What Is a Patent?

An issued patent gives you the legal right to exclude others from producing, selling, or using the specific thing you invented. Because this is a potentially powerful exclusionary right, Congress decided that patents would be granted for a limited term only. The patentee must also fully (and publicly) disclose their invention in the patent so that once its term expires, others may practice the invention. More on this in a bit.

The U.S. patent system was established by Benjamin Franklin. He and others foresaw that granting patents would encourage practical innovation in a young nation that might otherwise be dominated by Europe’s industrial might. In my non-expert opinion, despite its controversies and limitations the patent system has served our nation well; others better suited to offer economic arguments agree.[5]

A surprising number of people assume that having a patent – any patent – guarantees fabulous wealth. But a patent does not guarantee you will benefit in any way from your invention except by having the right to exclude others from practicing it. I’m a named inventor on several patents. If you happen to find that fabulous wealth I was supposed to get, please let me know.

Parts of a Patent

A patent document contains many interrelated parts. The body of the patent is called the specification. The specification is the descriptive portion of the patent minus the series of statements at the end called claims – more on those in a minute. The specification is where the inventors describe their invention, the unmet need(s) it addresses, its advantages, and how it is distinguished from previous inventions. In many ways the specification is like a technical publication. The disclosure includes one or more preferred embodiments of the invention, e.g., specific examples of the patented device or method.[6] Many if not most people assume that the specification is the patent’s most important part. We’ll disabuse you of that assumption in a moment.

The specification must meet two criteria. The first, called enablement, means that the specification must be written in sufficient detail that someone working in the field could build or practice the invention. This is part of the patent’s “legal contract”: in exchange for an exclusionary right, you must fully disclose what you’ve invented. And the specification must meet the written description requirement. This means the specification must provide evidence that the inventors actually made the invention. For example, in a first patent the invention may comprise multiple elements, and the inventor asserts that all of these were already known in the field of practice, but their combination is novel. Then in a later patent the same inventor claims to have invented one of these elements, asserting it was heretofore unknown in the field.[7] Clearly, the inventor didn’t “have” the invention at the time they submitted the first patent application. This can cause problems for the inventor down the road.

A patent generally includes several figures. These can clarify the specification, serving as the proverbial picture worth a thousand words. I often peruse the figures first when reviewing a patent. Flowcharts are especially helpful when reading patents comprising methods.

All that said, the claims are the most important part of the patent. While the specification is often written wholly or mostly by the inventors, the claims are written by patent agents or attorneys. This is because the claims define the legal the scope of the invention, and therefore bound the inventor’s rights. A patent claim specifically points out the subject matter claimed as the invention. It will embody both technical language and legal convention. A skilled attorney will write claims that are as broad as possible, consistent with the material laid out in the specification. Broad claims mean the patent covers more of the field of practice and is therefore (potentially) more valuable.

There are broadly three types of patent claims:

- A claim for an invention – for example, a device,

- A claim for a method of producing an invention – think of these like a recipe,

- A claim for a method of implementing an invention – for example, computer instructions embodied as software residing in a memory that cause a computer to perform a process – with many exceptions and qualifications!

Each of these claim types can be independent or dependent. An independent claim stands on its own and can be thought of as a very terse legal description of the invention. A patent may contain more than one independent claim. Dependent claims depend on one independent claim and limit the scope of its invention to more specialized forms. Dependent claims are always read along with the claim upon which they depend. You can think of their union as one long(er) claim that describes a more specialized or limited invention, perhaps one that uses a specific material, or a particular processor, or has a certain size, or additional functionality not disclosed in the independent claim.[8]

Since they are so important, how do you read a patent claim? This can be a challenge given their sometimes-awkward wording. Start by reading the claim language in terms of its plain and ordinary meaning, e.g., just the words as written and commonly understood in the patent’s field of practice. If that’s not clear enough read it in light of the other claims since that can sometimes resolve ambiguities in meaning. Should that not work, read the claim in light of the specification. The claim must apply to at least one preferred embodiment disclosed there. Looking for correspondences between the words in a claim and parts of the disclosure can often clarify awkward claim language. And finally, if all else fails you can dig up the so-called patent prosecution history to see if it sheds any light on the claim. The prosecution history is the publicly available record of all written back-and-forth communications between the inventor and the patent office during the examination process. If after all this you still can’t make heads or tails of the claim it might be considered “insolubly ambiguous,” and ripe for being disallowed in a subsequent legal proceeding.

Practically speaking, you cannot claim to have invented something not disclosed in the patent. This may seem obvious, but sometimes an inventor and their patent attorney aren’t on the same page. The inventor may expect the patent to cover things that it simply does not. There are other things you cannot claim to have invented, either. You cannot claim to have invented any laws of nature or natural phenomenon. Abstract ideas are not patentable. Mathematics is not patentable. Neither is computer software except as noted above.

Please note that the precise meanings of many terms elaborated above and in what follows are matters of law. Arguments over the precise meanings and scope of these terms are not mere word play or abstract legal theory. The terms are significant because they define the bounds of an inventor’s legal rights. For those of us who aren’t lawyers or patent agents, this means the patent process is best served if we stay in our respective lanes. Inventors can work productively with patent attorneys if they understand something of the process. We are also subject matter experts who can help a court or court officer understand the technical matters in a patent dispute. Just leave the lawyerin’ to the lawyers.

Eligibility, Expertise, and Prior Art

When the patent office reviews a patent application, they must consider whether what is being claimed is novel, useful, and non-obvious in light of what has been done before. Two of these criteria are established considering so-called prior art, which we’ll discuss below.

An invention is considered useful if it has a useful purpose. The invention must also be operable; it must actually work. You might understand our nation’s Founders’ interest in this metric. An invention that did not have a useful purpose wouldn’t contribute to the nation’s growth and prosperity. I can almost see Benjamin Franklin’s disapproving glare.

Novelty is established by what a patentable invention is not. For example, the claimed invention was not known, or used by others in the U.S. before the applicant invented it. The invention was not described in any printed publication – including another patent – before the applicant invented it. And the invention was not in public use or on sale in the U.S. more than one year prior to the patent application’s filing.[9] This isn’t an exhaustive list; there are qualifications, additions, and limitations to these criteria. But it should give you a general idea of what “new” or “novel” subject matters is.

Non-obviousness is perhaps the most difficult criteria to meet, or even define. A new invention may differ in one or more ways from a previous invention. Great! Those differences may satisfy the novelty requirement. However, the patent application can still be disallowed if the differences between the two inventions is obvious, or if the differences between the invention and some combination of prior art is obvious.

There has been much legal kerfuffle over the precise meaning of obvious.[10] To my non-legal mind it comes down to the differences, and how these differences are assessed. This assessment is left to a hypothetical individual referred to as a person of ordinary skill in the art. This person is someone to whom an expert in the field of the invention could assign a routine task with reasonable confidence that it would be successfully carried out. They themselves are not experts. Rather, they are someone who could read the patent and practice the invention. Looking through this person’s eyes, and based on their knowledge and experience, obviousness asks whether they would find the difference between the claimed invention and the prior art so insubstantial that they would find it obvious to make any changes needed to create the applicant’s invention.[11]

I slipped in a term that bears closer examination: the field of the invention. This is another legal concept that I understand as an engineer and inventor. I recall reading an opposing expert’s report where they asserted (in essence) that an invention was obvious because we have access to printed and online publications of all sorts, so the patented invention was just a combination of things from all those sources. His argument was an example of hindsight. Given a patented invention one can use the patent itself as a sieve to comb through the immense body of knowledge we can access, and likely find all the component pieces of the invention. This is like standing in the middle of MIT’s Barker Engineering Library, arms outstretched,[12] and saying, “Look at all these books and journals! Everything about your invention is in here… somewhere. Therefore, what you did is obvious.” Note that combining various pieces of prior knowledge can itself be inventive. The field of the invention, then, is used to narrow the person of ordinary skill’s skillset to those technologies relevant to the invention. Otherwise, we run into the Barker Library scenario where all knowledge could be prior art.

A Few Paddling Patents: US Patent 4,133,285

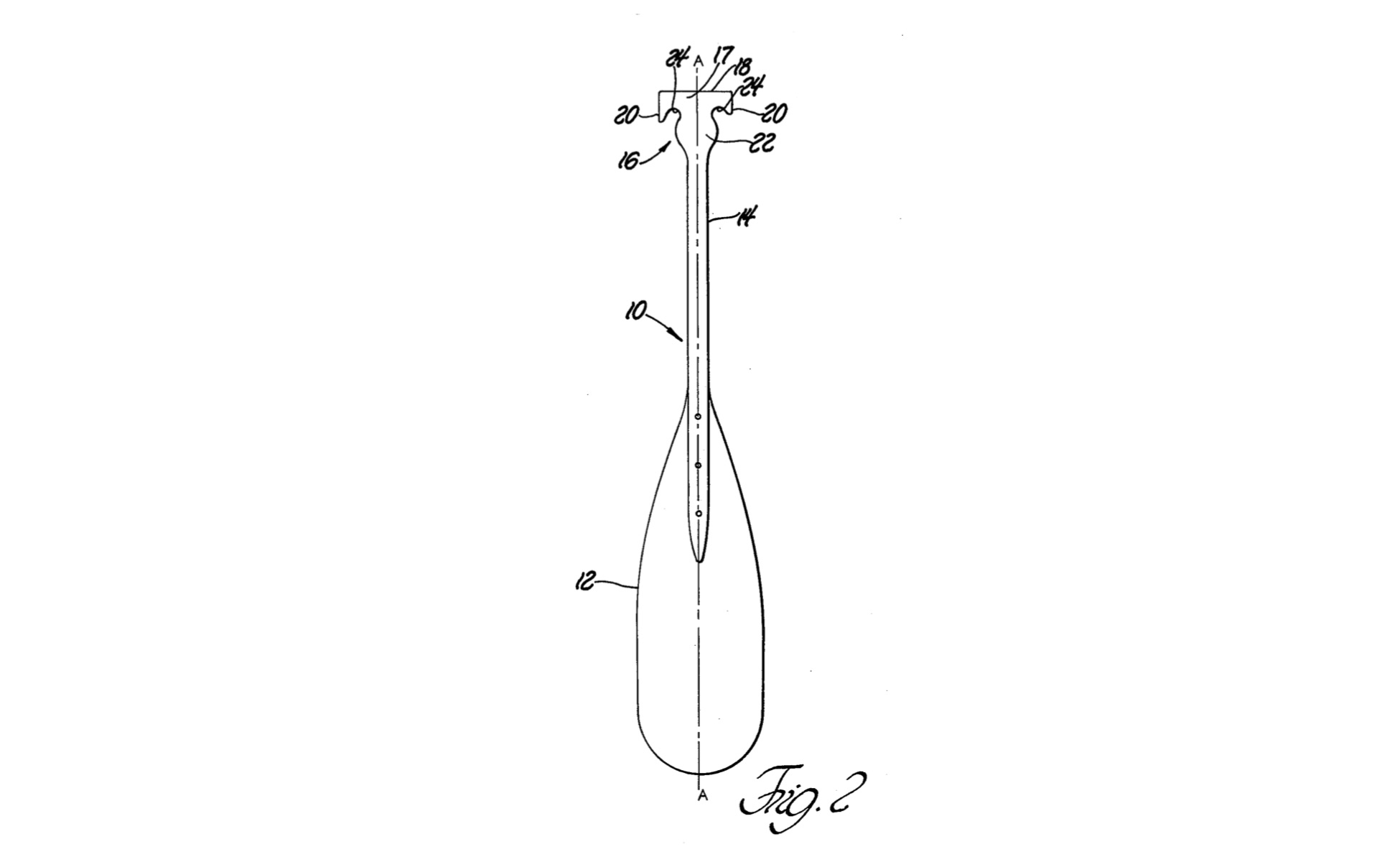

With those preliminaries out of the way, it’s time to read some paddle patents. We’ll begin with US patent number 4,133,285 titled succinctly as “Boat paddle.” This patent’s Fig. 2 appears in our Fig. 2 below.

Figure 2: US 4,133,285 Fig. 2.

This patent’s first independent claim 1 follows. I’ve split the original text so that we can parse its phrases more easily.

A paddle for manually propelling a watercraft such as a canoe,

This is the claim’s preamble, which provides context for the invention’s intended purpose.

said paddle comprising a blade, a handle and an intermediate portion connecting said blade and said handle, said blade, handle and intermediate portion having substantially a common axis,

Like all canoe paddles we see the usual parts: blade, handle, and shaft, all in a line (“a common axis”). These are labeled as elements 12, 10, and 16 in Fig. 2.[13]

said handle comprising an unencumbered edge transverse to said axis to be grasped by the canoeist’s fingers and a contoured edge providing a saddle against which the base of the canoeist’s thumb can exert pressure when the handle is gripped, said saddle being spaced from said axis such that substantially all of the fingers can grasp said edge, said handle being generally T-shaped and comprising a cross member at the end of said intermediate portion normal to said axis, said cross member having discreet projections at the ends thereof extending toward said blade and generally parallel to said axis,

This describes the T-grip-like portion that the canoeist’s fingers wrap around, comprising elements 17,18, 10, and 24 in Fig. 2.

said intermediate portion having a wider flattened portion at said handle adapted and positioned so as to be engaged by the canoeist’s lower palm when his fingers grip said transverse edge.

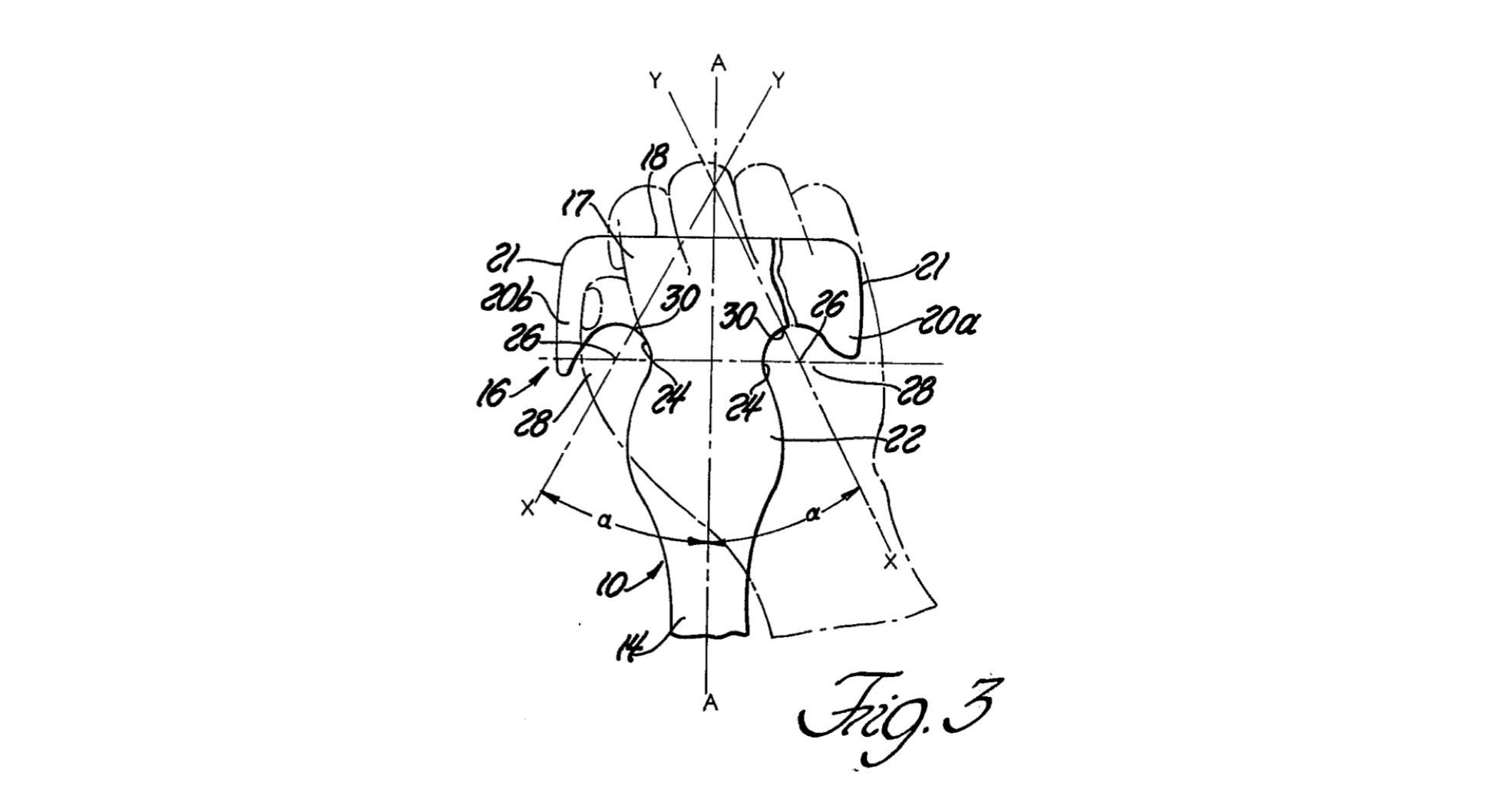

Their palm rests against something reminiscent of a “guide” paddle’s grip where the palm presses against a flat portion as depicted in Fig. 2 element 22. This is reinforced in Fig. 3 where we can see the envisioned hand position.

Figure 3: US 4,133,285 Fig. 3.

As you can see in the claim language, while precise and a bit awkward, is nonetheless readable if we take our time. This independent claim defines the invention as a canoe paddle built with a particular style of grip. Note that claim 1 does not specify the paddle’s length, material, or the blade shape. Consequently, all canoe paddles having the claimed handle design are “covered” by this claim irrespective of their length, material, or blade shape. This is then the “scope” of the claim.

A more limited embodiment of the invention is disclosed in dependent claims 2 and 4, which we’ll consider together:

2. A paddle such as that recited in claim 1, wherein the adjacent edges of said projections, said cross member and said widened portion are formed to provide a substantially circular or generally U-shaped slot at each end of said handle of sufficient width to receive the base of the canoeist’s thumb, said slot comprising said saddle and substantially preventing lateral thumb movement.

Dependent claim 2 specifies the shape of the handles recesses so that they fit the user’s thumb, and “prevent[] lateral thumb movement.” Claim 2 must be read along with independent claim 1. It defines the scope of a narrower invention than is described in claim 1.

4. A paddle such as that recited in claim 2, wherein the centerlines and sides of said slots form acute angles with said paddle axis, said angles approximately 45 degrees or less, but substantially less than 90 degrees.

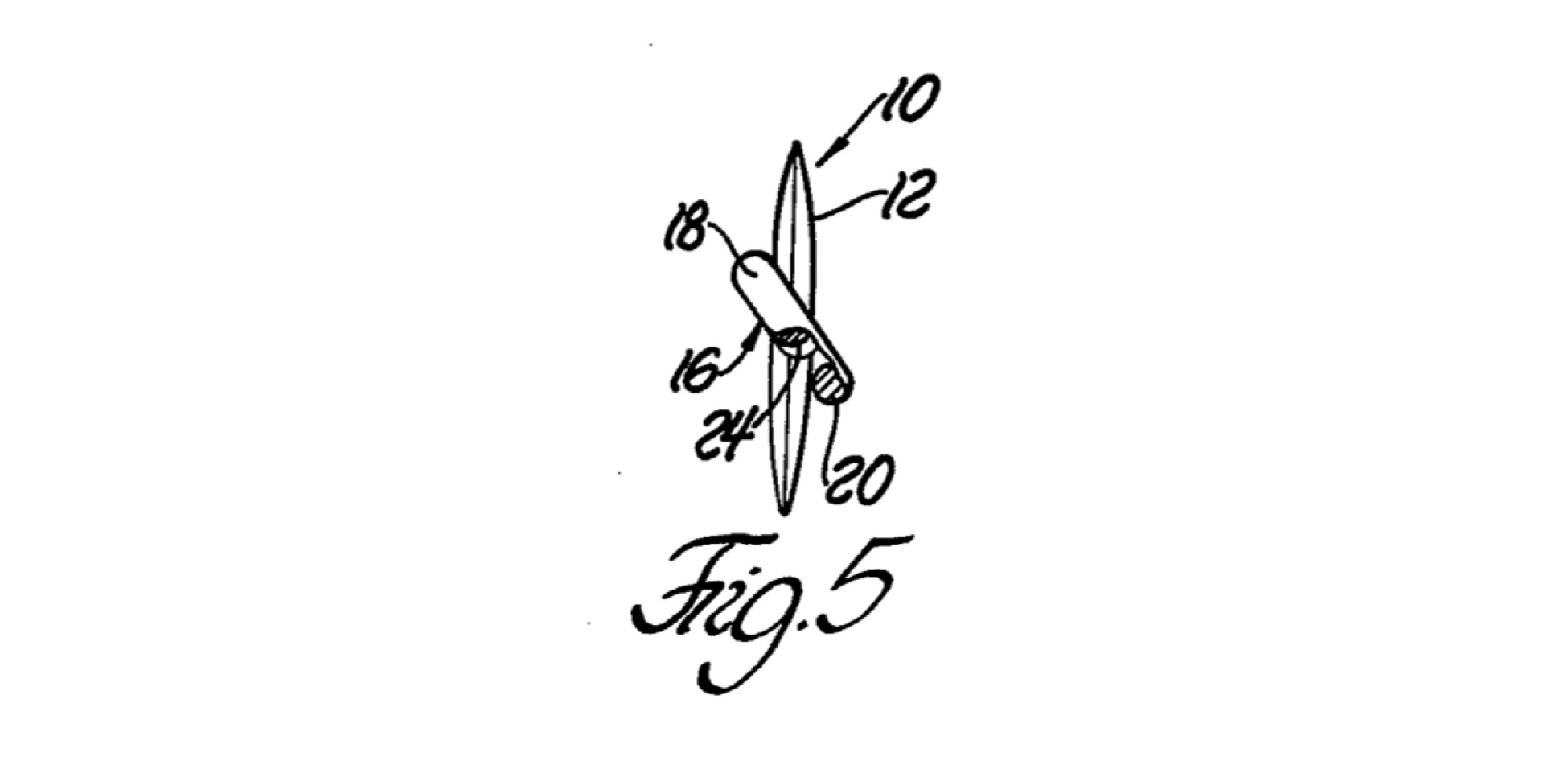

Dependent claim 4 depends on this claim as well as independent claim 1, and reflects the embodiment represented in the patent’s Fig. 5. Here, the grip (element 16) is set at an angle to the blade (element 12) as shown in (our) Fig. 4’s top view below.

Figure 4: US 4,133,285 Fig. 5.

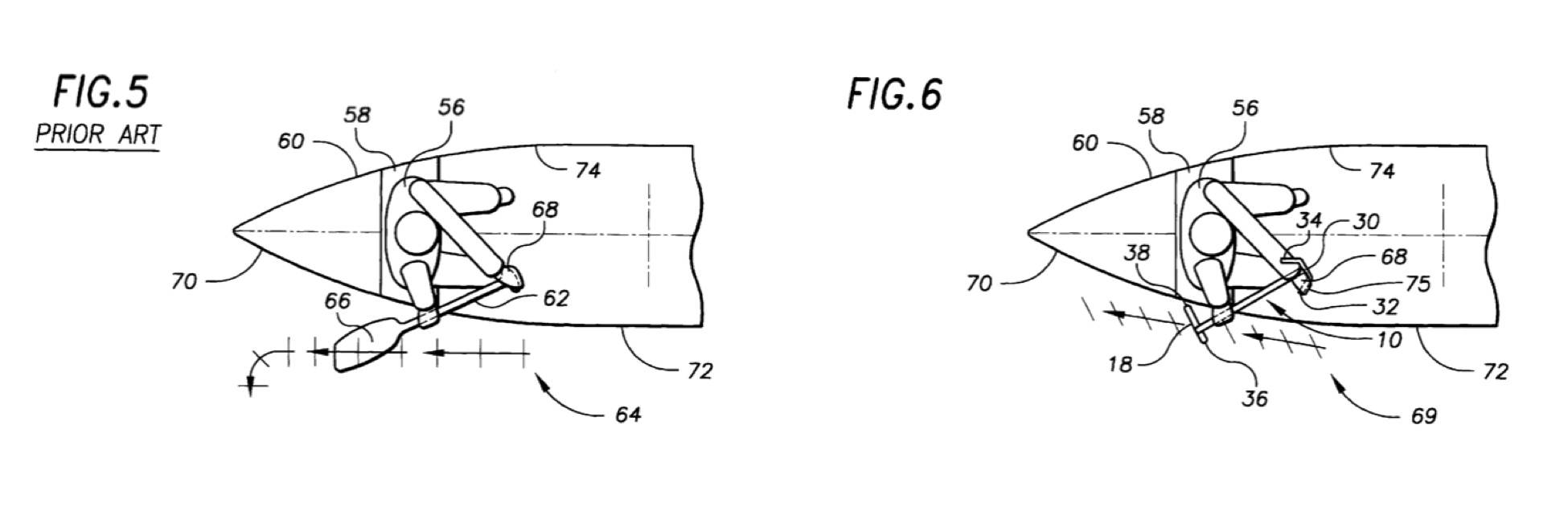

US Patent 4,303,402

US patent number 4,303,402 titled very succinctly as “Paddle.” This patent’s Figs. 1-4 appear in our Fig. 5 below.

Figure 5: US 4,303,402 Figs. 1-4.

Per the specification, this invention attempts to address the following unmet need:

In the manufacture of paddles and oars, it is particularly desirable that they be light and at the same time very strong. This invention provides for a paddle made of lightweight synthetic and metal materials which also provide the paddle with strength and durability. The blade of the paddle is of a unique design and construction and is angularly displaced from the shaft of the paddle so as to provide increased stroke efficiency even though the paddle of the invention is lighter in weight and can be made shorter in length than conventional paddles manufactured.

We see that the paddle is a so-called “bentshaft” design because this will “provide increased stroke efficiency.” However, we shall see that the inventor does not claim to have invented this feature. The larger problem being addressed appears to be one of lightness and durability. Perhaps this paddle was intended for canoe liveries and other outlets where these are a very desirable attribute.

This patent comprises four claims. Claim 1 is an independent claim, while the others all dependent. Claim 1 is a bit long, and defines the invention as follows (with commentary):

A paddle for propelling a water craft,

The obligatory preamble.

said paddle comprising a blade, a straight shaft connected to said blade, and a handle placed on said shaft at an end opposite from said blade,

Like Gaul, this paddle is divided into three parts.

said blade being angularly displaced from the longitudinal axis of said shaft at an angle of about 7 degrees to about 15 degrees,

It’s a bentshaft

said blade comprising a cup portion including a flat bottom of triangular web-shape, two side walls substantially perpendicular to said bottom and a front lip portion connecting said side walls, said front lip portion being sloped away from said bottom, said paddle including a reinforcement portion contiguous with said cup portion and positioned between said cup portion and said shaft, said reinforcement portion being in a plane parallel to said shaft,

While this part of the claim is a mouthful, with a slow and careful reading you can see how it describes the embodiment depicted in Fig. 5 (the patent’s Figs. 1-4). The blade is hollowed out on the back face. It does not claim to have a concave power face. In fact, this is specifically precluded by the claim language specifying the blade as having “a flat… triangular web-shape.” Which means that if you built a paddle like this with a concave power face you have “invented around” this patent and may not be infringing the claim.[14]

The blade’s walled design and “reinforcement portion” would provide a fair bit of structural stiffness. Hollowing out the blade makes it lighter than an equivalent solid blade of the same thickness. These claim elements are consistent with the patent’s stated needs for a light weight and strong paddle.

said cup portion of said blade being angularly displaced from said shaft,

Yes, it’s a bentshaft.

said shaft being hollow and formed of lightweight materials selected from the group consisting of foam injected plastics and lightweight metal

A hollow shaft is lighter than a solid shaft of the same diameter. This feature is consistent with the patent’s stated goal. However, no mention is made of composite shaft materials, so this language limits the claim’s scope.

and said blade being formed from foam injected plastic.

As for the shaft, this is a particular material choice. Consequently, one may be able to “invent around” this patent merely by using a different blade material. I haven’t researched the patent’s prosecution history to see if this limitation was added to the claim during review. If so, it was probably introduced to overcome an objection from the USPTO’s reviewer. If not, the claim is written in an overly narrow way, and therefore has a narrower scope than, for instance, a paddle with blade made from a variety of materials, or where no particular material is named.

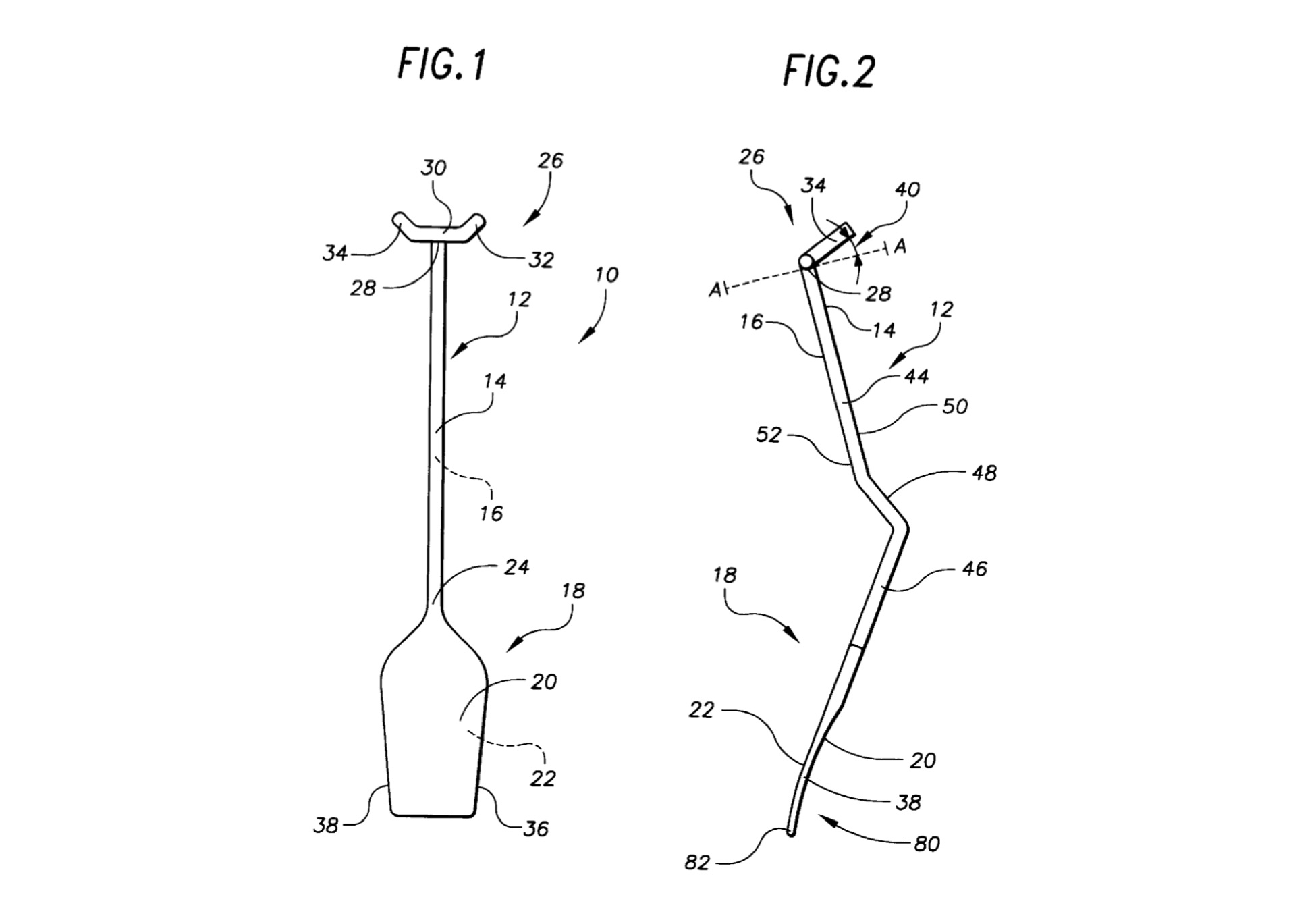

US Patent 6,042,438

US patent number 6,042,438 titled “Ergonomic canoe paddle.” This patent’s Figs. 5 and 6 appear in our Fig. 6 below.

Figure 6: US 6,042,438 Figs. 5&6.

Fig. 6 above (the patents Figs. 5 and 6) illustrates the patent’s goal and contextualizes it compared to prior art. Here, the prior art is a conventional canoe paddle, used to execute a J-stroke. The patent’s Abstract states:

the blade is disposed in an angular alignment that compensates for non-linear thrust of the paddle as the shear surface of the blade shears water to propel a canoe through the water.

First off, “shear surface” isn’t a term of art I’m familiar with re. canoeing. However, searching the patent’s specification I found “the shear surface of the blade to face a rear end of the canoe…” I can then infer that “shear surface” corresponds to the blade’s power face since the power face will “face a read end of the canoe” during the forward stroke. Similarly, the inventor discloses that the paddle blade has a “drag side” that is “opposed” to the shear side. Now that we’ve nailed down those two terms, we can try to understand what is meant by “non-linear thrust.”

The patent specification states:

One common approach to counter that non-linear thrust characteristic of conventional straight canoe paddles is to frequently switch the paddle from the starboard to port side of the canoe after several strokes…

Further,

In executing a J-stroke, as shown in FIG. 5, as the paddle nears the end of the stroke wherein the user’s arms can reach no further toward the stern of the canoe, the user rotates the paddle so that the flat surface of the blade, while still underwater, is aligned parallel to the direction of travel of the canoe. The user then pushes the blade away from the canoe before the blade is extracted from the water, thereby generating a counter turning force to the non-linear thrust of the conventional straight shaft canoe paddle.

I initially inferred that the “non-linear thrust” might be the corrective pry that occurs over the latter stages of a J-stroke. This prying element is directed away from the linear path of the paddle blade and might (emphasis on might) be considered “non-linear” in that it is not collinear with this path. However, the second excerpt above shows that this is not the case. The “non-linear thrust” is the reaction force due to the blade force that moves the canoe forward, but because it is performed at an offset from the keel line it causes the canoe to turn. This, the stroke causes the canoe to turn rather than proceed in a straight line. As you can see, we sometimes need to do a bit of spelunking to understand a patent’s particular lexicography.

A preferred embodiment of the invention is depicted in the patent’s Figs. 1 and 2, shown in our Fig. 7 below.

Figure 7: US 6,042,438 Figs. 1&2.

Now that we have the context, let’s look at the first independent claim element by element (with commentary) and see how it maps to this embodiment.

An ergonomic canoe paddle for propelling a light watercraft through water, comprising:

The preamble provides context for the invention. Note the word “comprising.” Patent attorneys tend to use this rather than “consisting of” since “consisting of” can imply that the elements subsequently disclosed are the only ones allowed. Think of “comprising” as “consisting of at least the following.” It’s one of my favorite words.

a shaft having a shear side and an opposed drag side;

Translation: a shaft having a power side and a non-power side. This is relevant here because the shaft has a complex shape, as shown above. The paddle has a preferred directionality given how it will be used to perform a forward stroke.

a blade having a shear surface and an opposed drag surface secured to a bottom end of the shaft, so that the shear surface of the blade is secured to the shear side of the shaft and the drag surface of the blade is secured to the drag side of the shaft; and,

The power face may be concave, as illustrated above, hence the concave power face must be on the same side of the shaft that is designated as its power side. Note that the claim does not specify a particular blade shape, concavity, or convexity. This makes it more broadly applicable.

a handle secured to a top end of the shaft, the handle including a central grip bar secured to the top end of the shaft, a right grip stem and a left grip stem secured to opposed ends of the central grip bar, wherein the right and left grip stems extend in a direction that is both away from the shaft and that is also away from the drag side of the shaft about twenty degrees to about seventy-five degrees from a plane defined as extending between opposed right and left edges of the blade and the top end of the shaft,

Consider the patent’s Figs. 1 and 2 in light of the top view in Fig. 6. The “handle,” what we might commonly call the paddle’s grip, is shaped like a bicycle handlebar. The handle starts as a T-grip at its connection to the shaft. Then it is bent at both ends, sweeping toward the power face side of the paddle.

so that when the left or right grip stem receives a user’s hand grip the shear surface of the blade is disposed in an angular alignment that compensates for non-linear thrust as the shear surface of the blade shears the water to propel the watercraft.

This element reflects how the paddle is held and used to perform a forward stroke, as illustrated in Fig. 6. When on the canoe’s right side, the paddler’s left hand grabs the grip’s outer portion. Given the grip’s shape and connection to the shaft, this will cause the paddle to rotate outward so that the blade’s power face makes an acute angle to the keel line.

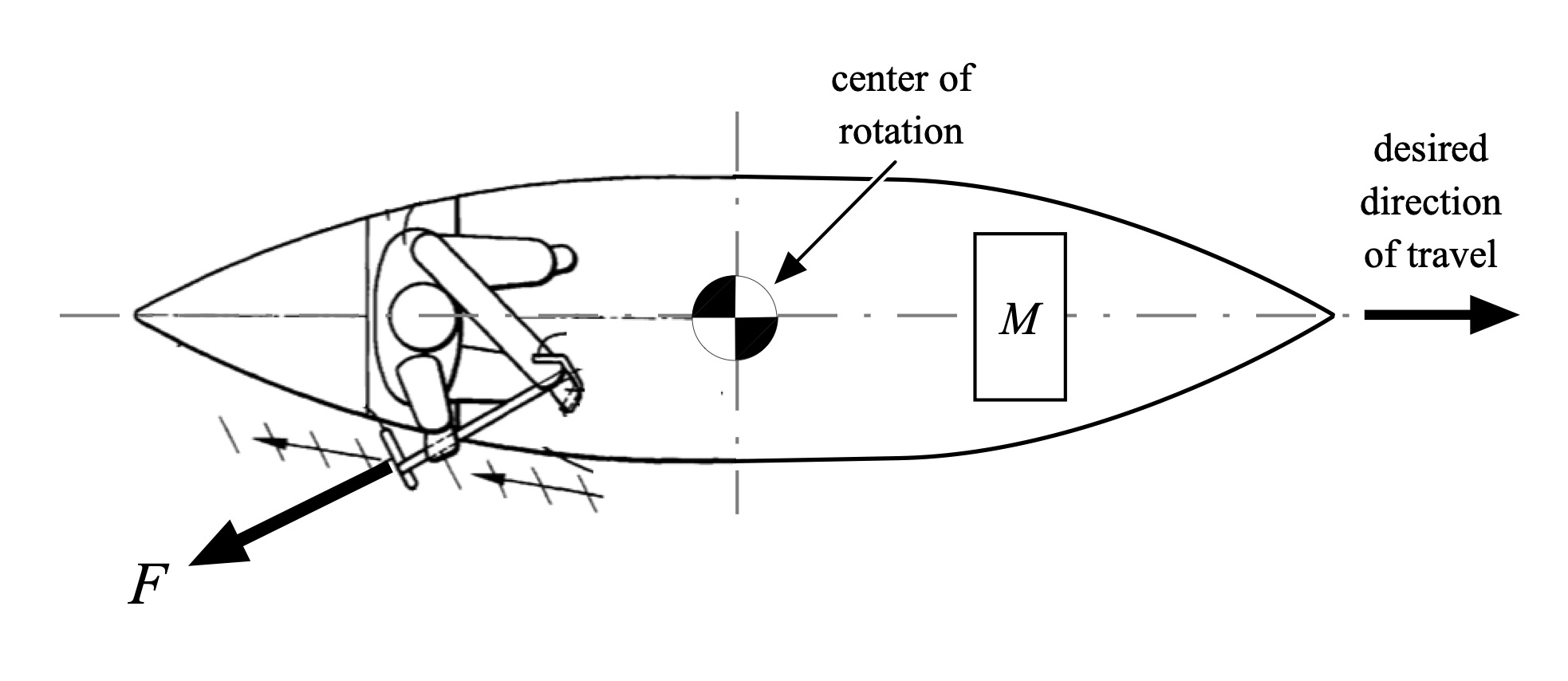

Whether this outward rotation will keep the canoe from spinning away from the paddle side is open to debate. Recall from Part 11: About the Bend that the blade exerts a force – which is a vector, and thus has a direction – perpendicular to the power face. This force can be decomposed into components along and perpendicular the direction of travel. So, consider an “updated” version of Fig. 6 where we now consider the whole canoe as illustrated in Fig. 8.

Figure 8: canoe, paddler, and paddle plan view.

So does the claimed invention “compensates for non-linear thrust as the shear surface of the blade shears the water to propel the watercraft.” I interpret this as meaning the paddler wishes to move the canoe forward in a straight line, e.g., in the desired direction of travel indicated in Fig. 8. The hull carries both a stern paddler and a weight of equal mass. This mass is set the same distance from the hull’s center of rotation as the paddler’s center of mass. Consequently, the hull as shown is symmetric in shape as well as mass distribution.[15] The paddle’s force vector is shown in the figure, perpendicular to the power (“shear”) face. While this vector translates when the paddler exerts a forward stroke, the indicated path of the paddle – essentially parallel to the gunnels – suggests that the force vector’s direction will be essentially the same throughout.

The paddle’s propulsive force has the same magnitude and opposite direction as the paddle’s force vector. It’s a reaction force; see Part 11. You can project a straight line through the force vector toward the keel line and see whether it intersects the center of rotation. If not, the propulsive force induces a torque around the center of rotation and causes the hull to turn. And even if the propulsive force vector intersects the center of rotation exactly, the hull will move in the direction of the force. That’s Newton’s Third Law in action. As you can see from Fig. 8 the only time the hull goes in the desired direction of travel is when the propulsive force vector is coincident with the keel line, e.g., in the center of the hull. Looks like our invention won’t meet its intended goal.

Or will it? Note the claim language, which states that the orientation of the power face “compensates for non-linear thrust.” Compensates does not mean exactly cancel. It just means the paddle should help offset the natural turning motion to some degree. The disclosed invention could do that. And while doing so it may also cause the hull to side slip away from the paddled side. I encourage you to do a vector construction using paper, pencil, and ruler to see for yourself is this is true!

Summary

In this installment of the Science of Paddling we’ve considered a particular type of IP (Intellectual Property): patents. After a thumbnail sketch of what patents are, and how to read them, we reviewed portions of three interesting paddle patents. I hope you now have the tools to read patents like this, appreciate their interrelated parts, and understand at a top level what a patent does or does not protect.

There are many reasons for obtaining a patent. Some of us work for companies or universities that routinely file patent applications covering their employees’ inventions. The only tangible asset many start-up companies have, aside from their founders’ expertise, is their patent portfolio. Since patents grant their owners an exclusive right to practice, a company may be able to fence off a particular product area while they develop the market for a new product. And there’s the purely intellectual satisfaction of having a patent granted and knowing that you (perhaps along with one or more colleagues) came up with a genuinely new idea.

You may even be able to sell your patent to a company that will bring your idea to market as a tangible product or process. If this entails fabulous wealth, please drop me a line and tell me how you did it.

Copyright (c) 2021, Shawn Burke, all rights reserved. See Terms of Use for more information.

References

Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP), https://www.uspto.gov/web/offices/pac/mpep/index.html.

- Sounds like a rip-roaring good time, eh? ↑

- These are patent numbers. ↑

- Note that I’ll confine my discussion to matters before the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Foreign patent offices have their own distinct standards and procedures. ↑

- Or we may choose to file our own patent and manage the process ourselves. If you’re interested in going that route, check out Pressman and Blau’s Patent It Yourself. ↑

- Stephen Haber, “Patents and the Wealth of Nations,” https://stephen-haber.com/wp-content/uploads/Haber-GMLR-2016.pdf (2016). ↑

- The patented invention is not limited to these embodiments, however, since the metes and bounds of the invention are disclosed in the claims. The claims often have broader scope than the preferred embodiments. ↑

- Note how the written description requirement and enablement overlap in this case. If the first patent required something that didn’t exist to work, nobody would be able to practice the invention. ↑

- This is where good patent attorneys earn their keep. A well-written independent claim has broader scope than its dependent claim(s). Broader scope can be more valuable, as noted above. However, if the independent claim is disallowed in a legal action the narrower dependent claim may survive, and the patent may still have value. ↑

- Note that these criteria don’t prevent someone from patenting an improvement to another invention. That’s perfectly fine if the “improved invention” meets the criteria. ↑

- Does this imply that the meaning of obvious isn’t obvious? ↑

- There’s more to obviousness than this, but it will get you started. ↑

- OK, I added the arms outstretched part for dramatic effect. ↑

- The numbering of these elements help you find corresponding descriptive text within the patent’s specification. ↑

- Note that I didn’t say this would not infringe the claim. This conclusion would be a matter of law, and I’m not a lawyer. My opinion as a person of ordinary skill in the art of paddles is that this would be the case, and I would offer that opinion to a court if asked. But the court construes the precise legal meaning of the claim (a process called claim construction), and a jury decides whether infringement has occurred, not me. ↑

- We’ll also assume that the hull is hydrodynamically symmetric fore and aft. ↑