by Shawn Burke and Kevin Olson

PREFACE

In this, the first installment of 2021, we’re joined by marathon paddler and personal trainer Kevin Olson of CanoeRaceWorld. We’ll be sharing a top-down approach to planning your training year. You might think of it as “training for engineers” because it addresses the questions, “Why am I training this way?” and, “Why am I doing this particular workout today?”

In concert with this article, Shawn has released software to plan and log training that mirrors the periodization concepts presented here. Kevin is using it with his paddling clients to plan their training year. You can learn more about that here.

Note that this article presents a structured way of planning your training year, and it’s very top-down. After reviewing general training concepts we move through goals, periodization, training cycles, ending up with your training week. There are other approaches to planning, and if you have one that you like by all means use it.

INTRODUCTION

To prepare for canoe races, you need to develop each of the following capabilities:

- Aerobic capacity,

- Anaerobic threshold,

- Technique and efficiency,

- Speed,

- General strength,

- Power, and

- Muscle endurance.

Obviously, you can’t train all of these attributes at once! The question now is when to train each, in what volume, and in what proportion?

In order to meet the variety of training needs, you’ll need to develop a plan. Or not; I know a number of successful racers who train more intuitively, listening to their bodies as they go. But for those of us who have Type ‘A’ personalities, a training plan provides a roadmap for your training: A good map shows you where you are at every point along the way, where you’re going, and how to get there. Planning takes time, but a solid plan, conscientiously executed, facilitates balanced development of the metabolic, muscular, and neurological systems, tied to your personal paddling goals. Planning also engages you in the training process so that you understand not only what you are doing on any specific day, week, or month, but also why you are doing it. This way you can adapt or prioritize your training as schedule or other interruptions arise, adapt and change it, and still achieve your training goals. And by having a plan you can track your progress and make adjustments in emphasis as appropriate.

TRAINING PRINCIPLES

Before we get into the nuts and bolts of creating a program let’s spell out the underlying principles that are the foundation of any effective training protocol. These principles should be kept in mind when designing your training program. They work in concert with each other to produce desired results, plus they provide guidance and a big picture view of your plan.

- Overload: To make improvements, you must increase stress levels from training that are more than your current athletic abilities. This can be accomplished by adding volume or intensity. If you fail to add volume and/or intensity, your body will not have the necessary stimulus to make further improvements/adaptations.

- Progression: The body is only able to handle a certain amount of stress at one time and improvements in performance are made over time. The concept of progression is adding small amounts of overload over time. If someone wants to increase the strength of their deadlift from 100lbs to 300lbs, you cannot just lift 300lbs and expect to be able to lift it. You will need to increase the weight you can lift in small increments over time that will lead to larger improvements the longer you add progressive overload.

- Adaptation: This is sometimes also referred to as the “repeated bout” effect. Your body will adapt to a specific stress the more often you perform that given task. An example would be if going from not running to running 3 miles; after the first bout you can expect to be sore, but if you consistently run 3 miles your body will adapt to this stress and be able to perform without getting sore. The more you perform an activity, the more your body becomes ready to handle that stress load. The load becomes less taxing as well.

- Specificity: The adaptations that your body makes are specific to the training stress that is applied. The closer a performed activity is to the goal activity the more improvement you will see in the goal activity. Going back to our deadlift example, if you want to deadlift 300lbs, running 3 miles will not help because it is not specific to the goal. Another example is running, which will have some carryover benefit to paddlers – running is an aerobic activity, and both running and paddling primarily rely on the cardiovascular system. But paddling will elicit a better overall adaptation as it uses a set of muscle groups specific to paddling.

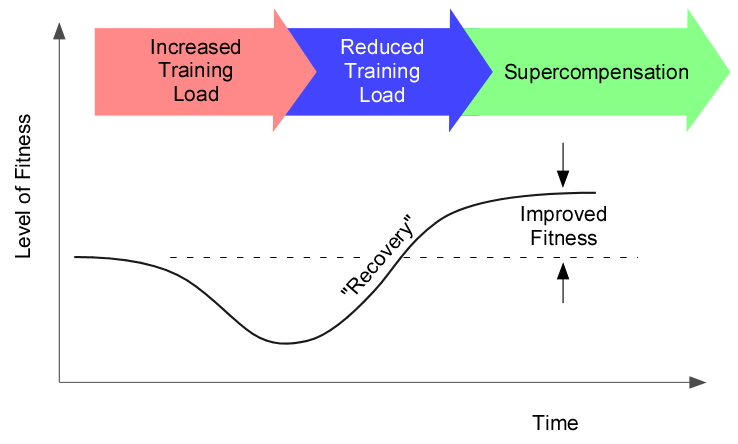

- Reversibility: Any adaptations that have been made through the consistent training will reverse if training is suspended. The longer training is suspended, the more your training adaptations will dissipate. All adaptations are not lost immediately, but if you do not train for months, you will lose most if not all of your adaptations from the previous season. Note that suspending training is not the same as reducing training load. In order to realize the so-called training effect (aka, supercompensation) you need to periodically give your body a break from high load training.

In net, we’re trying to leverage these principles to take advantage of the training effect, as depicted conceptually in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The training effect.

APPROACHES TO PLANNING

The ancient Greek Olympians were perhaps the first to train for sports in a methodical fashion. They reasoned that training should build in volume gradually over time, with peak efforts achieved just prior to competition. This approach appeals to common sense, and does work.[1]

No significant new approaches to training schedules were developed until the beginning of the 20th century. At that time a number of Russian coaches theorized that it was best to divide the training year into three phases: a general preparation phase emphasizing overall strength and fitness, a specialization phase where the specific elements of the sport were trained, and a competition phase. This was an early example of what we now call functional periodization. Later, Soviet track and field coaches emphasized skill/strength periodization, where the movements of the sport are taught and perfected before being applied at greater intensities in subsequent training phases. Each of these approaches has achieved success in its particular niche and time period.

Contemporary approaches to training divide workouts into two broad categories: general training, including aerobic and general strength training, and so-called “quality” training, which includes tempo, interval, threshold, and speed work as well as strength training for power and muscle endurance. The notion is to lay a base of general fitness that builds in volume until a few months prior to competition, then begin to taper the overall training volume while increasing the proportion of quality work. This has recently been supplanted by training philosophies that simultaneously increase total volume as well as the volume of so-called “quality” work over time, with a tapering phase the few weeks prior to competition. As you can see, there are perhaps as many approaches to planning your training program as there are trainers and coaches.

What we’ll review here are ways to periodize your training. Periodization is the process of dividing your training into a series of functionally distinct phases, each one building on the previous to achieve the ultimate end result of maximum performance. That said, there are no “one size fits all” approaches to training and periodization. However, if you design your own training program rather than copying a fixed program out of a book, you’ll know both why you are training in a particular way, as well as how to revise the program on the fly as you assess your progress. That’s our goal.

There are some general guidelines for all paddlers who wish to develop their own training programs:

- Paddlers seeking to develop general endurance and strength are well served by training programs that emphasize aerobic workouts and whole-body circuit weight training. Enter a local race or two and have fun. Or plan a multi-week backcountry trip, and know that you’ll be fit to paddle those long miles – and carry those long portages.

- Newer racers should first build an extensive aerobic base, then introduce interval work to develop speed and aerobic capacity. Anaerobic training sessions need not continue for an extended period of time to reap benefits; 8 weeks prior to the start of racing season, with increasing sharpness over that time, will more than suffice. As time permits novice racers should do circuit training and some max strength training. It is reasonable for them to dispense with strength training when spring arrives to maximize on-water time. On-water training should emphasize good paddling form and technique.

- More experienced racers will want to maintain (or increase) their aerobic capacity, and will incorporate anaerobic training into their workouts fairly early on. Specific types of strength training will be dictated by developmental and racing needs. For example, “grinders” may wish to develop more paddling-specific power and speed for starts, shallows, and surges. And “sprinters” may wish to develop more muscle endurance for long-distance events.

- For all racers, training during the competitive season will decrease in volume from the preparatory phases, and increase in intensity; it’s all about anaerobic threshold and the ability to utilize your available aerobic capacity. This reduced volume works well for those of us who have finite amounts of time to train, as well as family and other commitments as summer approaches. Fortunately, when paddlers are aerobically fit they can maintain much of their aerobic base with primarily anaerobic training, plus some over-distance maintenance and recovery work.

How Much Should I Train?

There are no easy answers to the universal questions, “How should I train for Race X?” and, “How many hours of paddling should I put in before Race Y?” These are matters of experience, prior training, available time, ability, and expectations. To at least bound the question seek out an experienced racer who has done the race and ask them for guidance. There is a big difference between just finishing a local race, and being a contender within your class. The important point is to be realistic. Consider the following before you start planning:

- What are your paddling goals this season? Write them down and review them periodically over the course of your training. These should include a hand of of qualitative goals, such as “improve aerobic endurance,” “improve boat handling,” and a far smaller number of quantitative goals, such as “improve time trial performance by 30 seconds,” “finish race X in under 2 hours.” The process of writing down our goals forces us to actually define, order, and prioritize them. Studies have shown that the majority of goals that are actually written down will be achieved with periodic review and assessment. As the saying goes, “if you can measure it, you can manage it.”

- How long have you been racing? Assuming that they have maintained their fitness, long-time racers will require less time to prepare than newcomers because their bodies have already adapted metabolically and neurologically.

- How many hours did you train last year? (Don’t know? Give it some thought. You might be surprised.)

- Were you satisfied with last year’s performances? Did you experience symptoms of overtraining? Do you feel that your training volume was about right, but perhaps you should change emphasis to improve specific areas? Or are you ready and able to put in more training this season than last?

- How much time do you have for training? This may be one of the most important questions. Will the time commitment permit you to fulfill other obligations in your life to your family, friends, work, community service, household chores, etc.? Neglecting any of these just adds stress, and life stress is another cause of overtraining symptoms. Remember, paddling is supposed to be fun!

In broad terms, recreational and novice racers targeting shorter, local races can have a great time and see performance improvements with around 3 to 4 hours of training per week, and annual training volumes from 100 to 200 hours[2]*. More advanced racers will put in 8 to 20 hours of training a week during peak periods, with annual training volumes from 300 to 400 hours. Elite racers can put in upwards of 700+ hours of training annually. Getting ready for an event like the Ausable Marathon 120-miler can entail 150+ training hours on the water alone. That’s like working a second job.

So, you’ve dug up your past year’s training logs (you kept a log, right?), dusted off your calculator, and figured out how many hours of aerobic, anaerobic, and strength training you did last season, as well as the total number of hours racing. Or at least you’ve estimated that total. We shall refer to this number as your annual training volume. If you feel that last year’s training volume was about right, then this will be your training volume for the coming season. If you found that you exhibited signs of overtraining last year, consider decreasing next year’s volume by 5% to 10%. If, however, you’re ready and would like to increase your training volume, use the following guidelines:

- 5% increase if you are reasonably fit but new to paddling for fitness or racing.

- 10% increase if you are fit and are an experienced racer or fitness paddler.

- 15% increase if you are extremely fit and very experienced, and can accommodate such a large increase in training volume without conflicts or injury.

Next, how long do you have to train before your big trip, goal race, or competitive season? This defines the length of your pre-season, which may include a few tune-up events. The most comprehensive way to approach training is lay out a yearly plan. That’s right, a whole year. Then, divide your training volume into phases that fit your schedule of goal events, races, competitive season, vacation, etc.:

- Decide what races you’ll enter in the coming season. Most governing bodies release race schedules in the early spring, but you can look at the previous year’s schedule to rough out your own race calendar. Or contact race directors of key events. Once you know when to be ready, in particular for a goal event, you can count backwards to determine when you should start training.

- If you are a newbie and have a good fitness base, it takes at least 2 months, and preferably 3, to prepare for just about any goal event. This is the minimum amount of time it takes to reap the benefits of the training effect. (And once you complete your event, why stop there? You’re not going to turn into a couch potato for the rest of the year, are you?)

- Many serious racers will spend 6 to 7 months preparing for the racing season, methodically building their fitness, adding more specificity and “quality” to workouts as the pre-season unfolds.

- Canoe racing season begins in the North in mid- to late March with downriver races, and can run into late October. A March to October race season is too long for most humans to maintain peak conditioning. However, since key races are often scheduled either early or late in the season, one option is to doubly periodize your training. That is, take a break in the middle of the season and build another aerobic base using primarily aerobic workouts. Do this over a four- to eight-week period; the more races you enter in the early season, the longer this rebuilding period should be. Then use local races to hone skills and race strategy, and keep your edge. Incorporate more quality work as championships approach late in the season. Then enjoy the local late-season races.

Given these broad concepts, the ensuing sections will show how to develop a training program that helps you work within these constraints. The exposition that follows uses a top-down approach, where we first present the overall structure of the training year, then break it down into major phases, then major training cycles within each phase, until finally we design training weeks. The approach mirrors that of Rob Sleamaker, in his excellent book, SERIOUS Training for Endurance Athletes.

MUSCLE METABOLISM AND TRAINING EMPHASIS

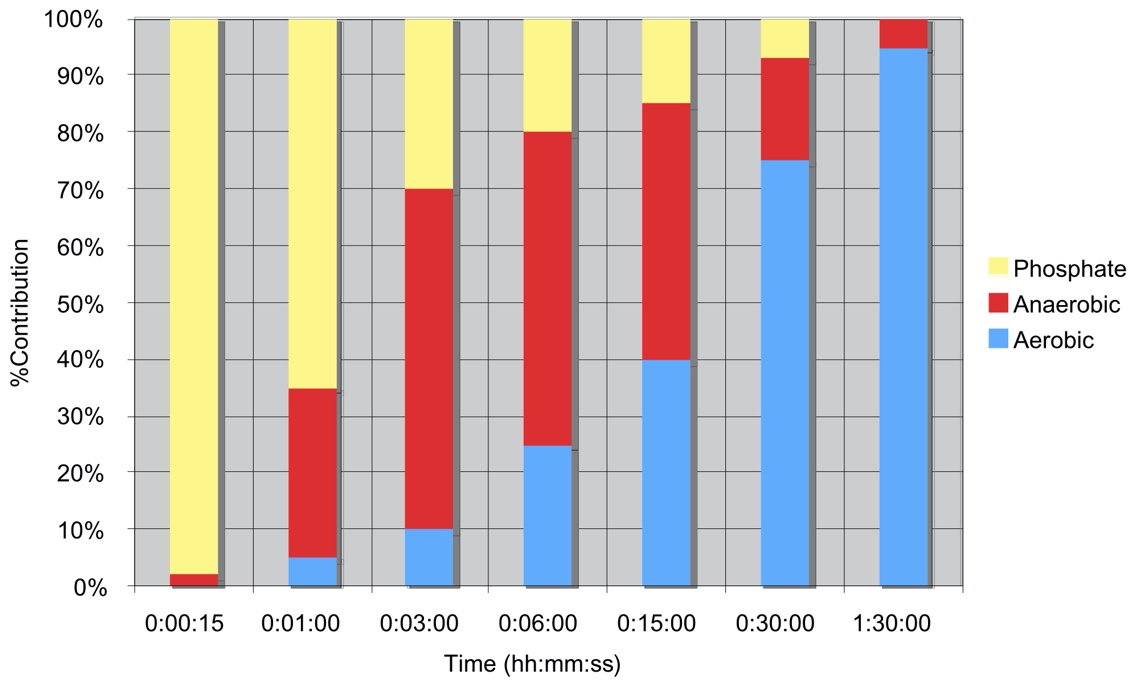

As we saw in Part 6: What Fuels You, the body employs the aerobic, anaerobic, and phosphate energy systems during exercise. Their proportional engagement depends on the length and intensity of effort. The relationship between the duration of exercise and the percentage share of the various energy systems is illustrated in Fig. 2. As shown in the Figure, short sprints are anaerobic and alactic, primarily engaging the phosphate system. A 400-meter sprint will slightly engage the aerobic system; however, energy supply is still dominated by phosphates and the anaerobic system. As races get longer the aerobic system becomes the dominant source of energy.

Figure 2: Energy utilization vs. time (after Janssen).

Fig. 2 suggests that you should train each of the energy systems in proportion to how it is engaged for a goal race’s length. In other words, an athlete training for a marathon should spend the majority of their training volume developing their aerobic system, and a much smaller fraction training their anaerobic system. Sprint training to optimize the phosphate system isn’t all that relevant for marathoners. Janssen’s model suggests that a 5k runner would train their sprint (phosphate) system 10% of the time, their aerobic system 70% of the time, and their anaerobic system 20% of the time. A paddler training for the 70-mile General Clinton regatta should prioritize training aerobic capacity. As the season progresses, and this paddler begins to participate in shorter races, training can emphasize anaerobic threshold and even sprint training as dictated by new goal race distances.

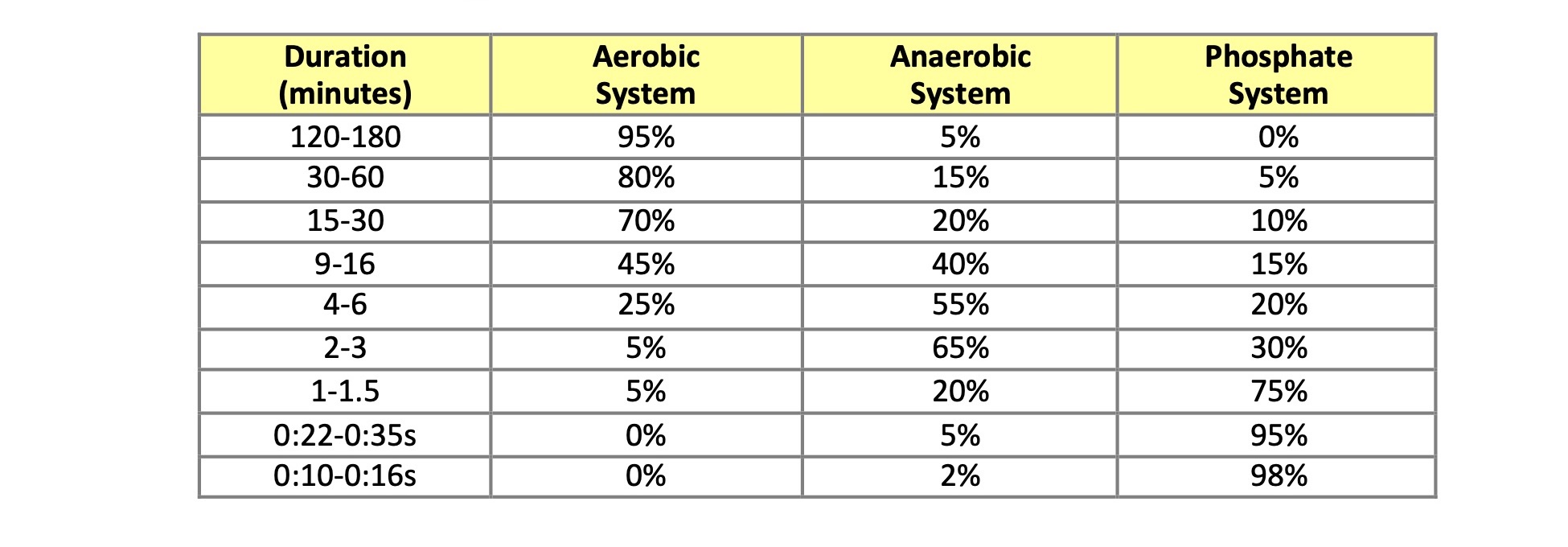

Table 1 breaks down how much each metabolic system is used for maximal efforts during races of various lengths. This table is the basis of how we’ll structure our training in what follows.

Table 1: Energy Utilization for Various Race Durations (after Jansen).

–

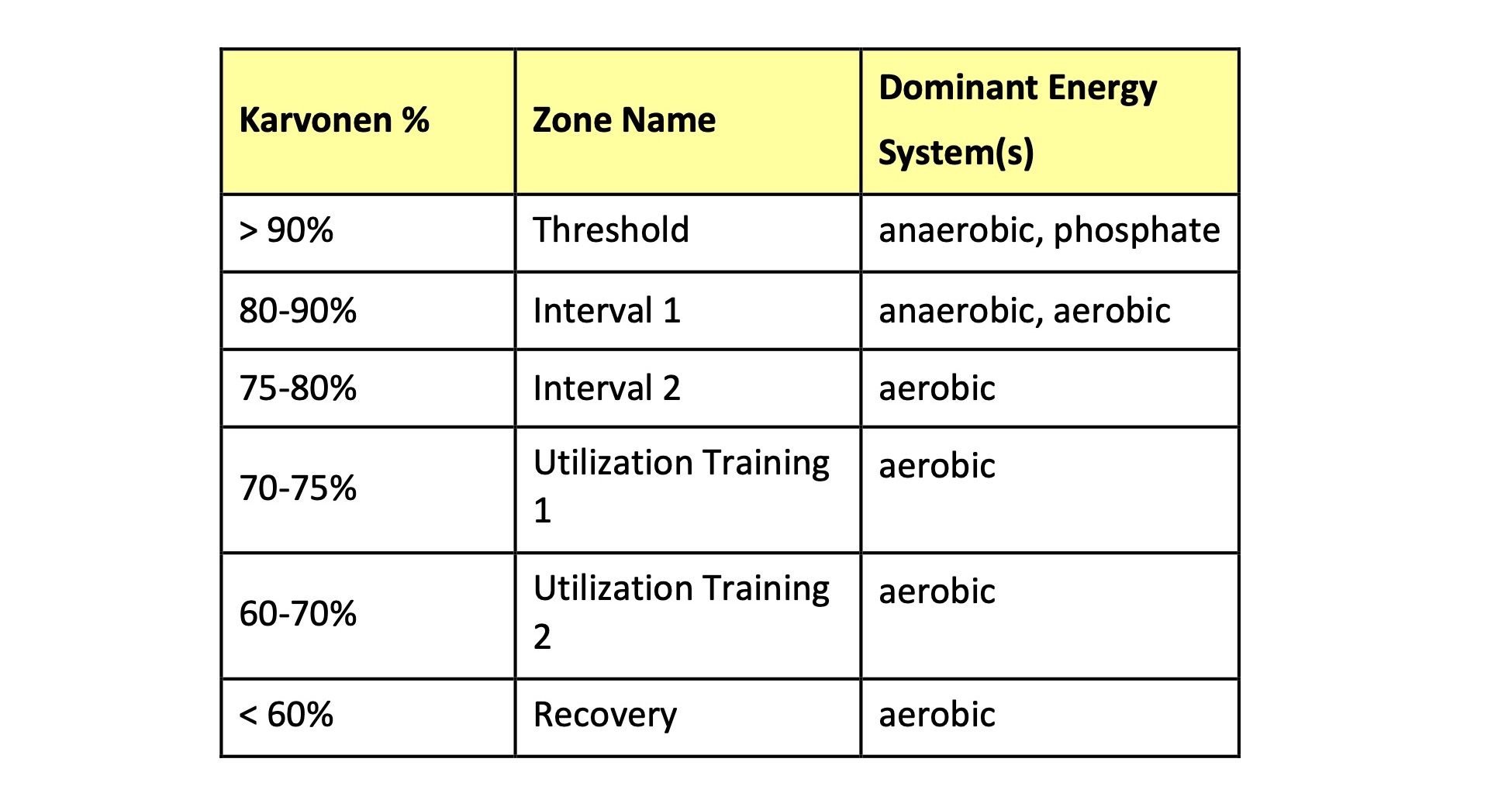

Karvonen Training Zones

So you have a heart rate monitor, and would like to use it to target training zones. Researchers have been able to link heart rate with aerobic, anaerobic, and alactic metabolic ranges with reasonably good accuracy. They did this by testing scores of athletes: measuring heart rate, oxygen uptake, pace, power, blood lactate, respiratory quotient (the ratio of carbon dioxide exhaled to oxygen inhaled), and the like while their subjects huffed and puffed on treadmills, cycling ergometers, rowing ergometers, etc. The resulting data was then analyzed to map out (in a statistical sense) the relationship between heart rate and exercise intensity. The resulting heart rate ranges represent averages that work fairly well for most fit people.

A popular means for defining heart rate ranges using this perspective is attributed to Karvonen. His approach is based on the concept of heart rate reserve, the difference between maximum and resting heart rate:

Heart Rate Reserve = HRmax – HRrest.

Think of your heart rate like the readings on a car’s tachometer. Heart rate reserve is analogous to the difference between idling and red lining the engine. Heart rate reserve is the range of heart rates over which you can exercise – or do anything for that matter! The so-called Karvonen method models exercise intensity in terms of the percentage of heart rate reserve that you use. A 100% effort corresponds to HRmax, while a 0% effort (e.g., rest) corresponds to HRrest. Now recall that HRrest decreases slowly over time as your fitness improves. In this way, the Karvonen method yields heart rate ranges that adjust to increasing fitness.

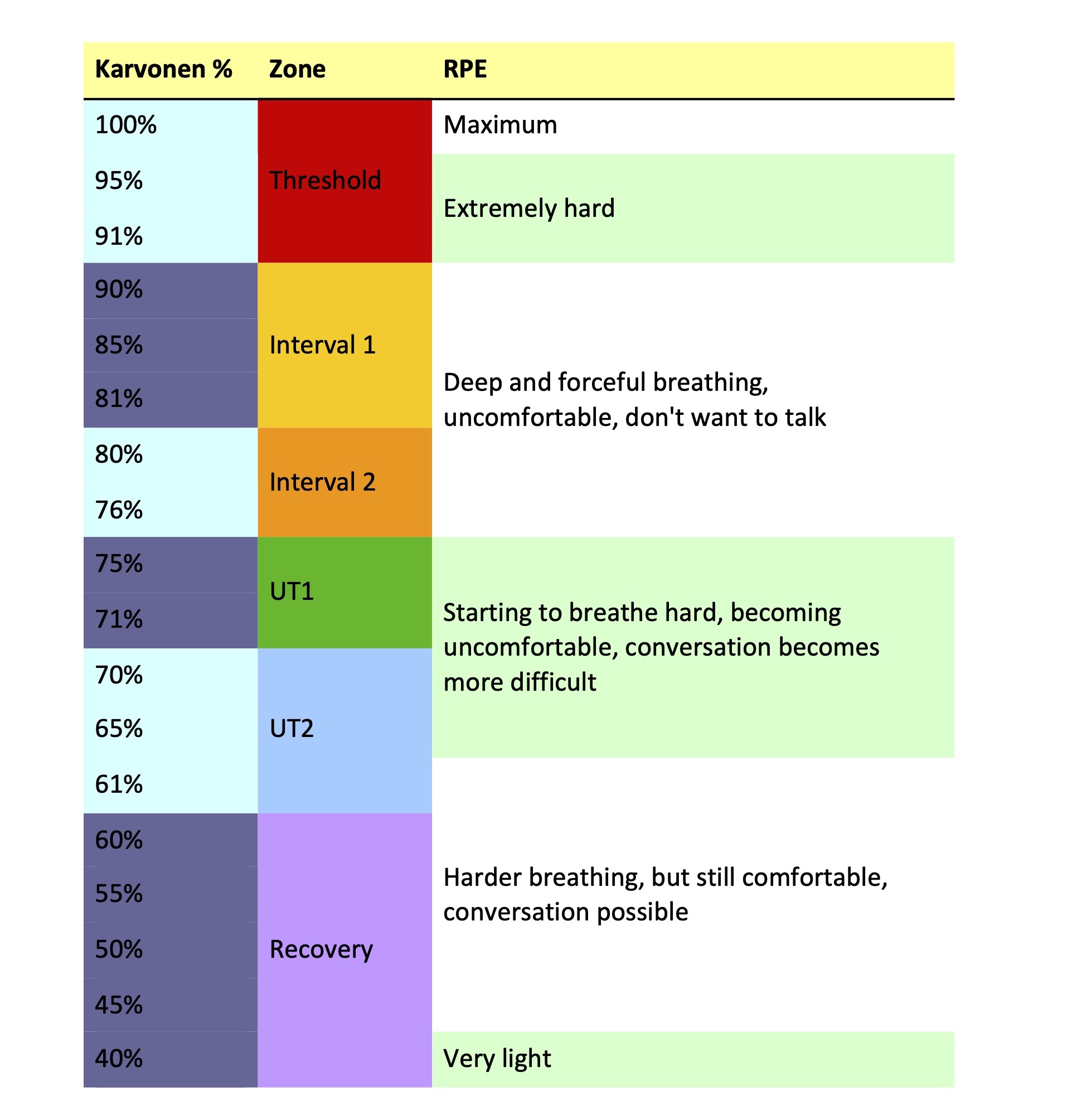

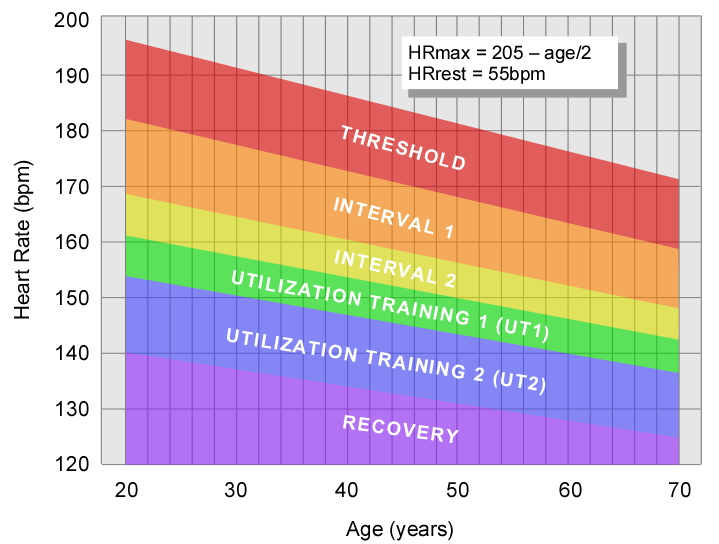

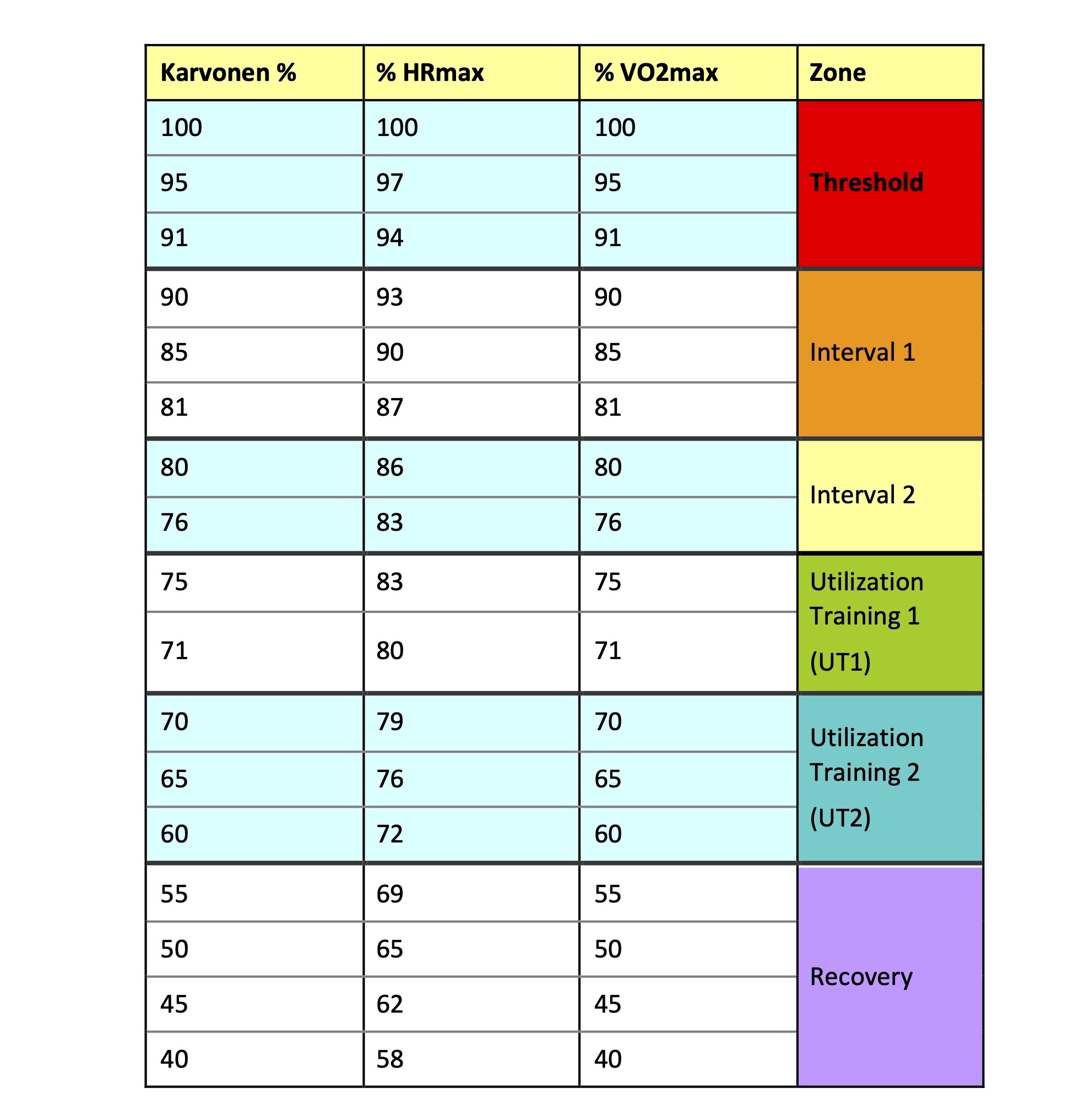

You can specify any number of Karvonen heart rate zones based on percentage ranges of heart rate reserve. One common approach is to define six zones that correspond to relevant levels of exercise intensity. These are summarized in Table 2. Note that the column header “Karvonen %” refers to percentage of heart rate reserve. The zone names are somewhat arbitrary; Rob Sleamaker calls the 70-75% and 60-70% zones “endurance” and “overdistance”, respectively. The categories “Utilization Training 1” and “Utilization Training 2” are after Janssen.[3] Again, note that the percentages in Table 2 are percentages of heart rate reserve, not percentages of maximum heart rate.

Table 2: Karvonen training zones.

–

Figure 3: Karvonen training zones vs. age.

These ranges are plotted in Fig. 3 using the model for maximum heart rate HRmax = 205 – age/2. A plot of the Karvonen training zones as a percentage of maximum heart rate vs. age would yield essentially straight lines (using either the 205 – age/2 or 210 – age/2 models for HRmax), even for a wide range of resting heart rates. Thus, the Karvonen ranges are essentially age-independent if represented as a percentage of HRmax.

Karvonen training zones are summarized in Table 3 for a paddler whose resting heart rate is 55 BPM (beats per minute) and maximum heart rate is 180 BPM. This is merely an example; your own data will likely be a bit different.

Table 3: Example Karvonen ranges as a percentage of max heart rate.

The Karvonen method provides a useful mapping between heart rate and metabolic energy system engagement, as suggested in Table 3.

We should season our conclusions about heart rate and exercise intensity with liberal doses of common sense:

- Karvonen training zones are based on statistical averages.

- Many athletes will have anaerobic thresholds higher than 90% of heart rate reserve.

- Training ranges based on heart rate don’t take into account the athlete’s anaerobic capacity, a trainable quality which shifts the anaerobic threshold.

- You can divide the percentage ranges of heart rate reserve in other ways, with more or fewer ranges. (But does that mean that you’re training is targeted any more accurately?)

- Very unfit individuals will become anaerobic during exercise at far lower fractions of heart rate reserve than predicted by the Karvonen method. These statistical models were developed using data from fit athletes.

Caveats aside, the Karvonen training zones nonetheless provide practical guidance when training based on heart rate measurements.

For those of you who don’t have a heart rate monitor, there is a correspondence between the Karvonen heart rate ranges and the so-called “Rating of Perceived Effort,” or “RPE.” This is illustrated in Table 4. RPE tries to quantify how an athlete feels at various levels of physical exertion. Since RPE is based on subjective ratings, use it with a grain of salt; what feels “extremely hard” may change from day to day based upon your state of rest and recovery, or your state of mind. That said, over time you’ll develop a sense of how your body is performing at various levels of exertion, and map our your own personal RPE.

Table 4: Karvonen zones and RPE.

–

PERIODIZATION

Training is best done in a season-specific, or periodized fashion, where training volume, intensity, and specialization increase over time to prepare the paddler for a goal event, trip, or competitive season. And since training is the combination of workload and rest, the training program should incorporate a recovery phase at the end so that you will be rested and ready to commence training for subsequent seasons.

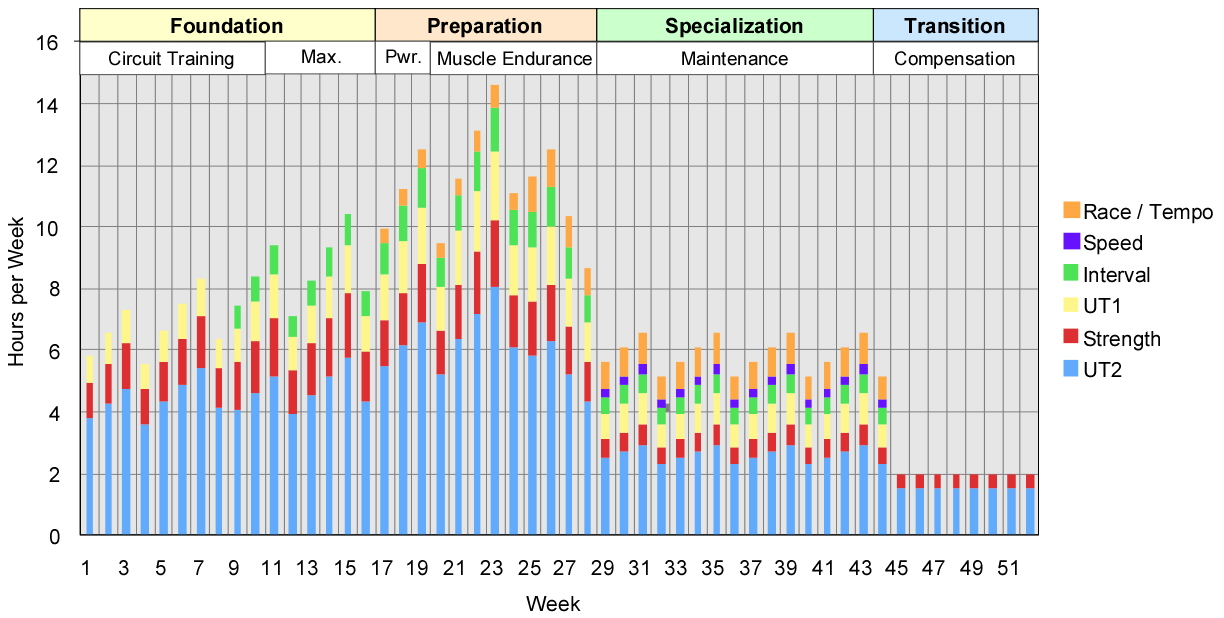

The four distinct seasonal training phases we will use are foundation, preparation, specialization, and transition. Within each phase there is a distinct mix of workouts consisting of various training elements, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Training volume is allocated among aerobic and anaerobic components based upon the fractional engagement of the various energy systems for a goal event, as presented in Fig. 1 and Table 1. The benefit of periodization is that by training the components of fitness individually and sequentially you can make greater gains in each component, develop the base for each succeeding element of training, and make gains in overall performance.

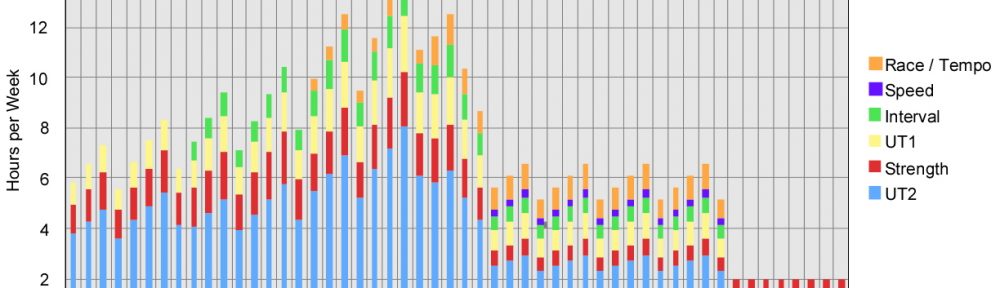

As shown in Fig. 4, training volume builds through the year, peaking during the preparation phase. At the same time training intensity continues to increase with the introduction of more quality work. The program depicted in Fig. 4 has a goal race following week 28 – the General Clinton Canoe Regatta. Training volume drops during race season and continues quality work.

Figure 4: Example of periodized training phases and training volume.

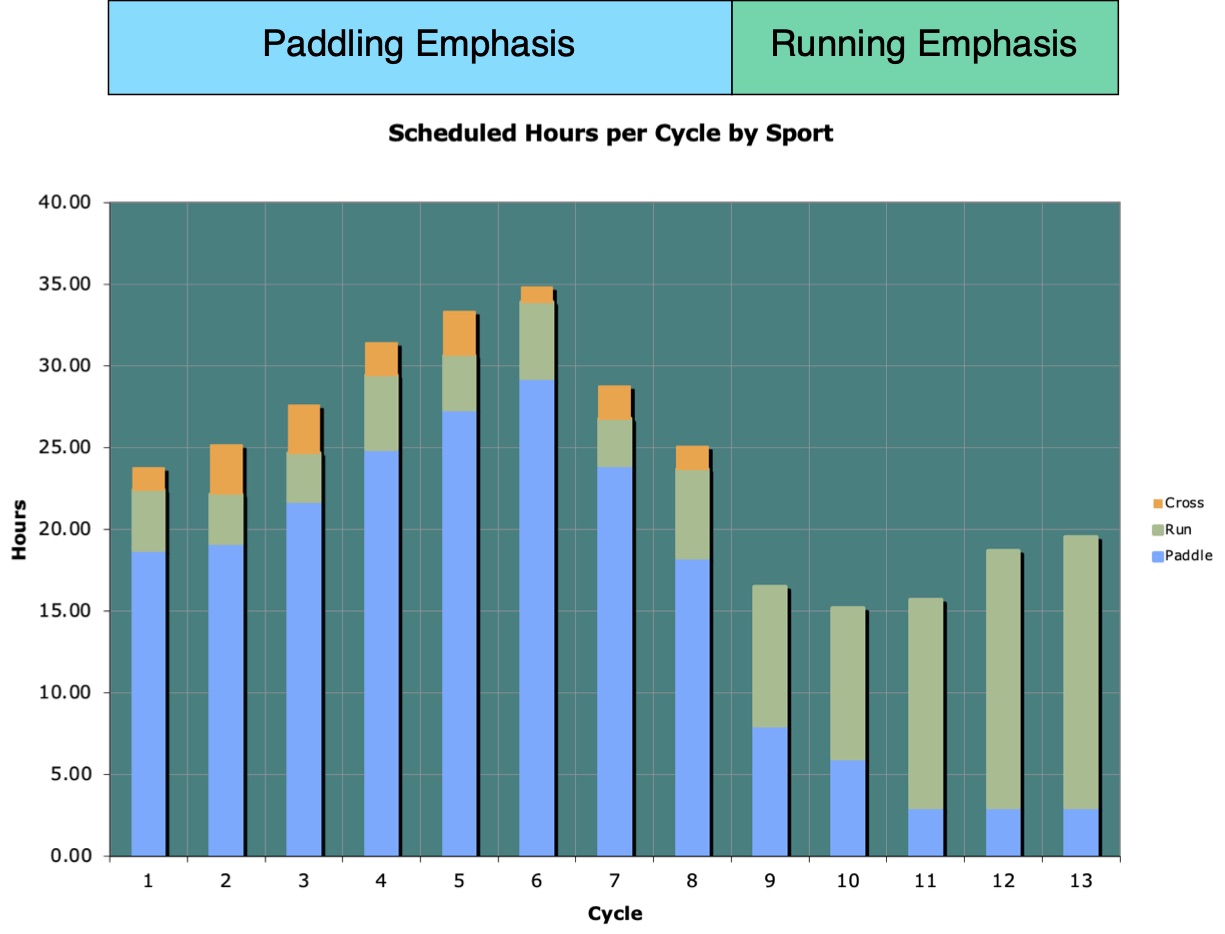

Now many of us will have more than one ‘A’ race on the yearly calendar, such as the Clinton and the Ausable. I’ve employed a split-year plan like that shown in Fig. 5 to focus my first 7 cycles of training on the 70-miler, with local whitewater and flatwater races along then way, and then shifted gears to target a late Fall half-marathon where now paddling becomes my cross-training.

Figure 5: Split year training concept.

The sample periodized training program presented in Fig. 4 corresponds to a 360 year-hour annual training volume. The four seasonal training phases are highlighted at the top of the Figure, along with the corresponding strength training phases. Your own training plan may have features in common with that shown in the Figure, but can differ depending on your goals and needs. For now, we’ll use the plan depicted in Fig. 4 as a model for discussing the elements of a periodized training year below.

Foundation Phase

The foundation phase lays the groundwork for the entire training year – you are “training to train.” The plan shown in Figure 4 has a 16-week foundation phase. Training during this period focuses on aerobic development, with some longer endurance workouts of moderate intensity. The key is to maximize the amount of energy derived aerobically while limiting the energy contribution from the anaerobic system to help ward off overtraining later on. Consequently, endurance training is primarily done at UT2 to UT1 intensity, with workouts lasting from a minimum of thirty minutes to two hours or more. Up to 15% of training volume can be devoted to cross training, and more if the foundation phase falls during winter months up north and you don’t have access to a paddling ergometer. Long intensive intervals (~85% HRmax during work interval) are introduced in the second half of the phase to work the central nervous system pathways with faster paddling; it’s always good to have more than one gear. Strength training during this phase begins with an anatomical adaptation phase, and concludes with a maximum strength phase for those intending to move into power training in the next phase. Recreational paddlers and new racers should focus on circuit strength training throughout the foundation phase.

The foundation phase will account for about one third of your total yearly training hours. So, if your target yearly training volume is 200 hours, about 67 hours will be devoted to foundation phase training.

Preparation Phase

The preparation phase introduces greater intensity into your workouts, focusing on the development paddling-specific power and VO2max capacity. The example plan shown in Figure 1 has a 12-week preparation phase. Short intensive interval (90-95% HRmax during work interval) training is introduced with successively shorter recover periods, as well as anaerobic threshold training, tempo workouts, and some short local races or time trials. The volume of training can grow depending on training needs and available time. Cross training is limited to about 10% of training mileage during this phase; some of this could include trail running – with your canoe if at all possible – to get ready for portages. Strength training during this phase focuses on power development and muscle endurance; recreational paddlers will continue to do circuit training, while newer racers will introduce maximum strength training and some muscle endurance work.

Note that the final two weeks of the preparation phase shown in Fig. 4 have decreasing training volumes. This taper was planned in anticipation of the General Clinton 70-miler on Memorial Day weekend. Tapering will be discussed below; suffice it to say that the reduction in training volume is designed to permit recovery before a long goal race.

This preparation phase in this plan accounts for about 36% of total yearly training hours. So, if the target yearly training volume is 200 hours, about 72 hours will be devoted to preparation phase training. While this sounds very much like your foundation phase training commitment, note that the preparation phase is typically lasts for half to two-thirds as long as the foundation phase. As a result, the monthly and weekly training volume in this phase will be higher.

Specialization Phase

The specialization phase is the competitive season. The plan shown in Fig. 4 has a 16-week specialization phase. The training intensity of this phase is high, with tempo work and anaerobic workouts done at 90%+ HRmax. Speed training is introduced. Workouts are shorter and paddling-specific; the overall training volume decreases along with the increasing intensity. Recovery workouts and rest are vital, along with some aerobic base maintenance. During this phase cross training volume should be reduced if at all possible. Depending on when races are scheduled, the specialization phase programming shown in Fig. 3 can be adjusted to incorporate short tapers and other variations, as discussed below.

The specialization phase in this plan accounts for about one quarter of the total year-hours of training. So, if the target yearly volume is 200 hours, this means about 50 hours working out in this phase. The monthly and weekly training volumes will be less than those of the preparation phase, on the order of the volumes found near the start of the foundation phase.

Transition Phase (The “Off Season”)

The transition phase is an oft-overlooked element of annual training programs. The preceding months of focused training takes a toll on the body and mind. The transition phase emphasizes recovery for the muscle systems engaged in paddling. However, this phase shouldn’t be seen as a prolonged vacation lying on the couch and binge-watching Netflix. If you completely stop exercising for a month, a rule of thumb is that it will take about two months to regain lost fitness.

The training goals of the transition phase are compensation – addressing undertrained parts of the body and functional asymmetries – and aerobic maintenance. This phase lasts from 4 to 8 weeks and should start with complete rest for 1 to 2 weeks with light, fun workouts such as hiking, roller blading, biking, etc. The balance of the transition phase consists of rehabilitation, compensation, and cross training. Total training volume is about half of what was performed during the foundation phase. Aerobic sessions are done primarily in a different sport than paddling to allow recovery of the paddling muscle systems and prevent (or treat) overuse injuries. For example, a dedicated paddler can spend time working on their (comparatively) neglected legs by biking, running, or hiking. The off-season also affords the opportunity to break out of the grind of racing and hard training, and give your mind a rest. Keep workouts aerobic – not anaerobic – and consider leaving the heart rate monitor at home unless you have a hard time keeping your workout intensity in check.

The transition phase in this plan accounts for about 5-10 of total year-hours of training. Volume is light, less than half of the specialization phase volume on any given week.

Training Cycles

Just as there are phases within the training season, there are cycles within each training phase[4]*. Training cycles typically last for 3 or 4 weeks. Consequently, a 16-week foundation phase would have four 4-week cycles, as per the example program shown in Fig. 4. The reasons for including cycles within the first three phases of the annual program is to progressively increase training volume week by week, and provide opportunities for recovery and consolidation to realize the so-called “training effect” of increased fitness.

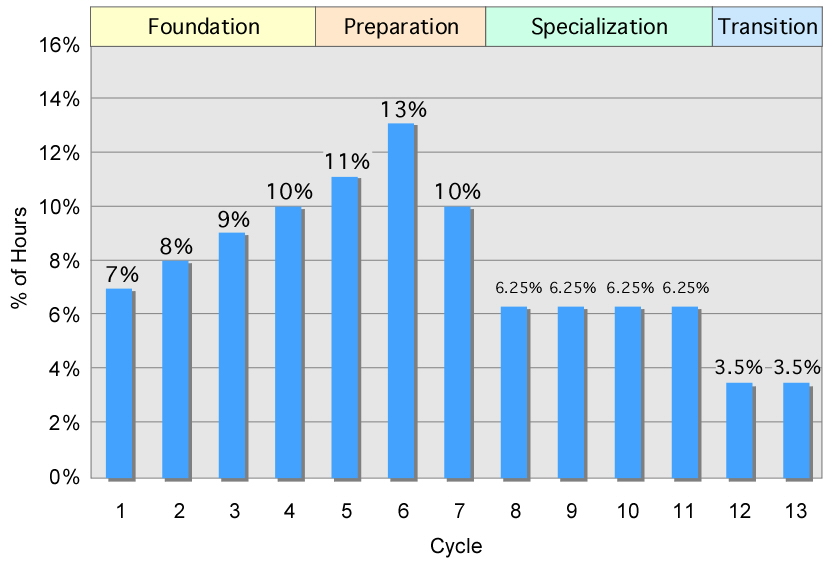

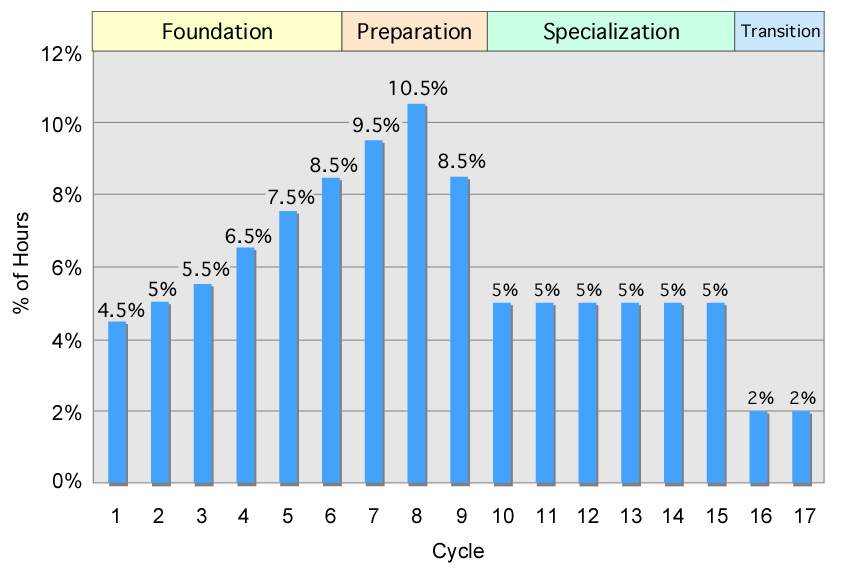

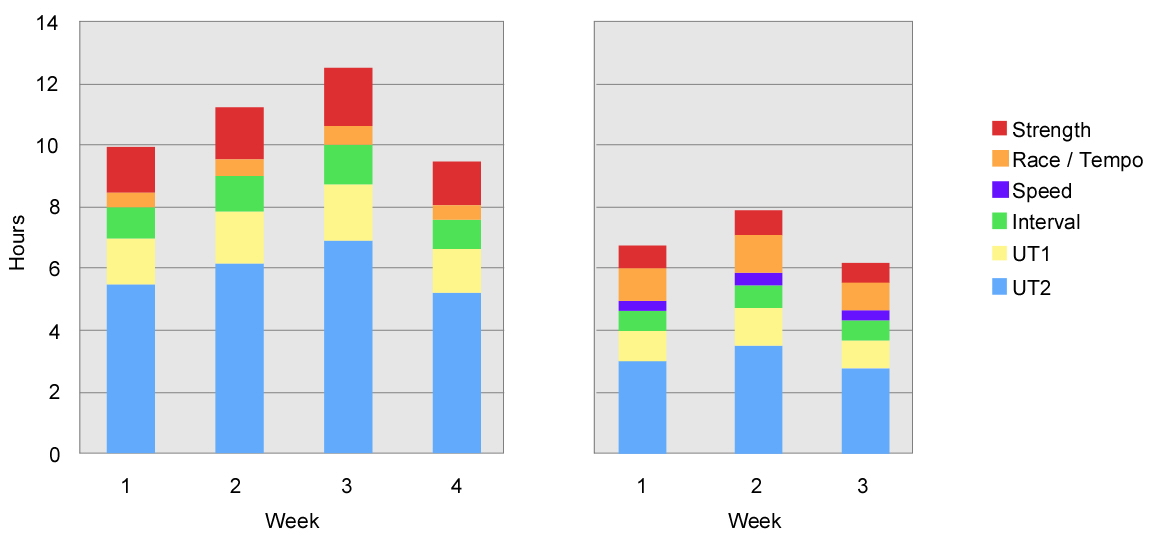

In order to program this increasing training volume we’ll use the so-called “10% Rule.” That is, training volume should increase cycle-to cycle by about 10%. As an example, one can distribute training time over a year using 4-week training cycles as shown in Fig. 6. Percentages of the annual training volume for each cycle appear atop the corresponding bar. A similar plot for a training year divided into 3-week cycles appears in Fig. 7.

–

Figure 6: Annual training volume variation using a 4-week cycle.

Figure 7: Annual training volume variation using a 3-week cycle.

A 4-week cycle increases training volume over its first three weeks using the 10% Rule. This is followed by a recovery week at the end of the cycle, e.g., a week of reduced training volume. Recovery weeks give the body a chance to rest and rebuild prior to the increased volume and/or intensity of the next cycle. Training is the combination of work and rest, and recovery weeks encourage the body to adapt and consolidate improvements made through training.

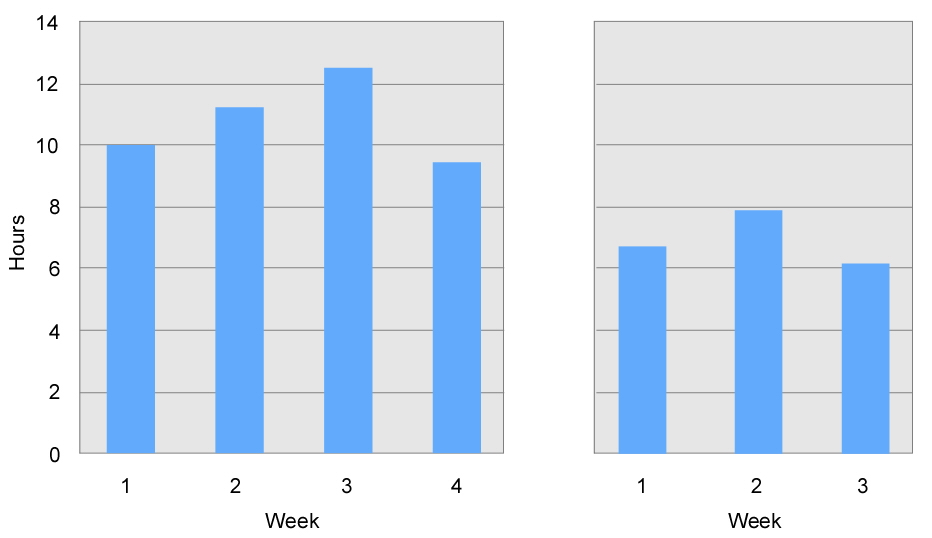

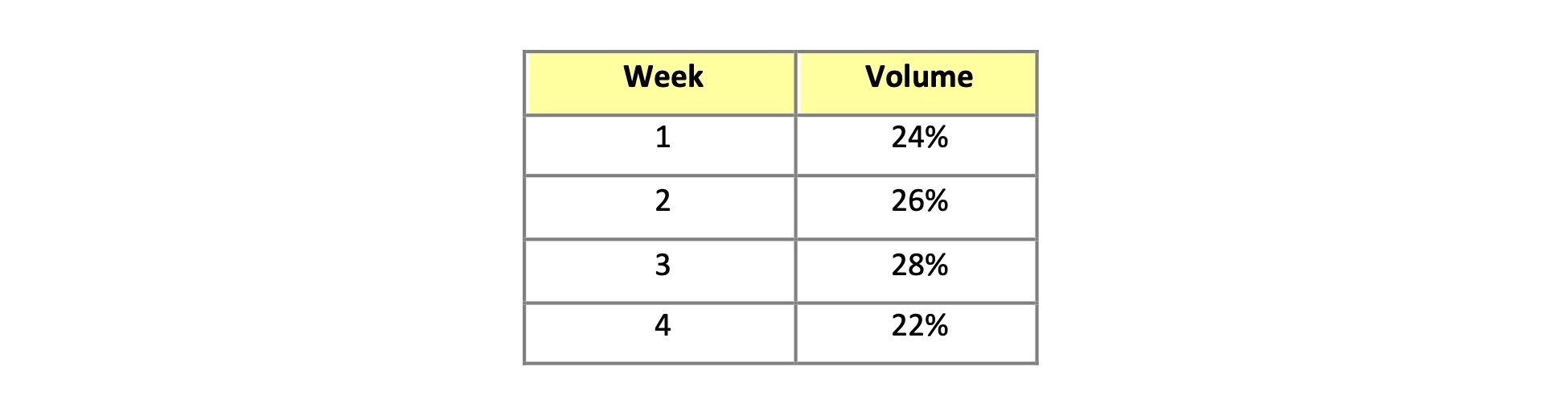

Examples of 4- and 3-week training cycles are presented in Fig. 8, showing the training volume in hours for each week within the cycle. Note that these variations in weekly training volume represent the weekly proportion of all hours allocated to the 4-week cycle. So if the training plan allocates, for example, 25 hours to this particular 4-week period, then week 1 would consist of 5:45 of work, week 2 has 6:30, week 3 has 7:15, and week 4 has 5:30. This particular percentage division of total workout time is fairly typical; alternatively, you can employ a 23% – 26% – 29% – 22% weekly allocation of workout time. The overarching goal is to follow the 10% Rule, and incorporate a recovery week at the end of the cycle. The recovery week should have a volume that is within 10% of the training volume of the first week in the next cycle. Again, workout volume should grow by no more than about 10% week-to-week.

Figure 8: Examples of 4- and 3-week cycles’ training volumes.

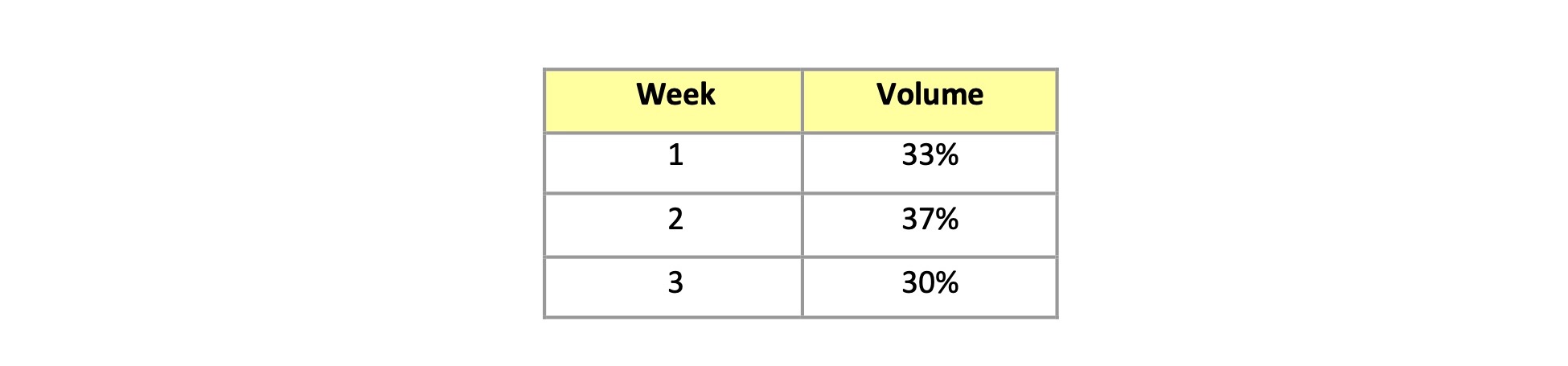

Within the 4-week cycle, overall training volume is typically allocated by week as shown in Table 5:

Table 5: 4-week cycle work volume distribution.

Using these same guidelines, a 3-week cycle’s training volume is allocated by week as shown in Table 6:

Table 6: 3-week cycle work volume distribution.

3- or 4-week cycles should be used during the foundation and preparation phases of your training plan. The cycle approach can be followed in spirit during the specialization phase, but variable event scheduling may make this difficult to achieve in practice without some juggling of workouts. Planning during the specialization phase should prioritize week-to-week volume adjustments so that you can taper properly before goal events. As always, follow the 10% rule during the specialization phase. While all of this might seem a bit opaque right now, by the time you’ve performed several cycles of foundation and preparation phase training you’ll have enough experience to allocate and adjust training volumes during race season. Examples are provided below in the discussion of the training week.

The weekly workout allocation during the transition phase is simple: keep weekly hours roughly uniform. The focus should be on variety. And fun.

WORK BREAKDOWN OF TRAINING PLANS

So you’ve determined your training volume, and have seen how to divide your training into functional phases. Within each phase training volume is allocated in 3- or 4-week cycles to build increasing fitness and ensure recovery. The question now is: How do you allocate the various types of training – aerobic, anaerobic, speed, etc. – within each phase, cycle, and week?

We shall define the allocation of workout type within a training period as work breakdown.[5] Work breakdown defines how you structure the various types of training over time. The work breakdown will change over the various phases of training, with an initial emphasis on base training that later evolves to include anaerobic training, speed work, tempo work, and racing. The programming of work breakdown should reflect your training goals regarding the type(s) of event(s) for which you are training.

Recall that the fractional engagement of the aerobic, anaerobic, and phosphate metabolic systems varies by race distance, as illustrated in Fig. 2 and Table 1. A long-distance marathon paddler’s training needs and associated work breakdown will consequently differ from those of a sprint distance paddler. One organizes the elements of the work breakdown based upon this fractional engagement.

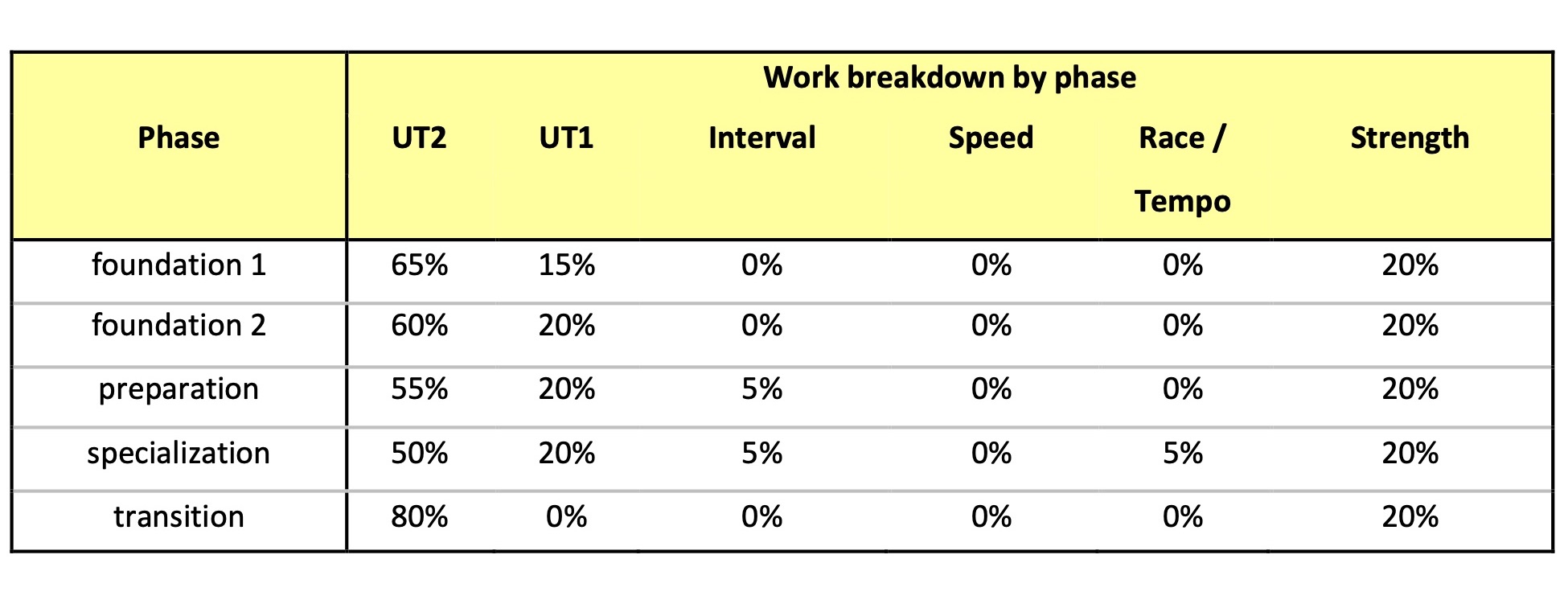

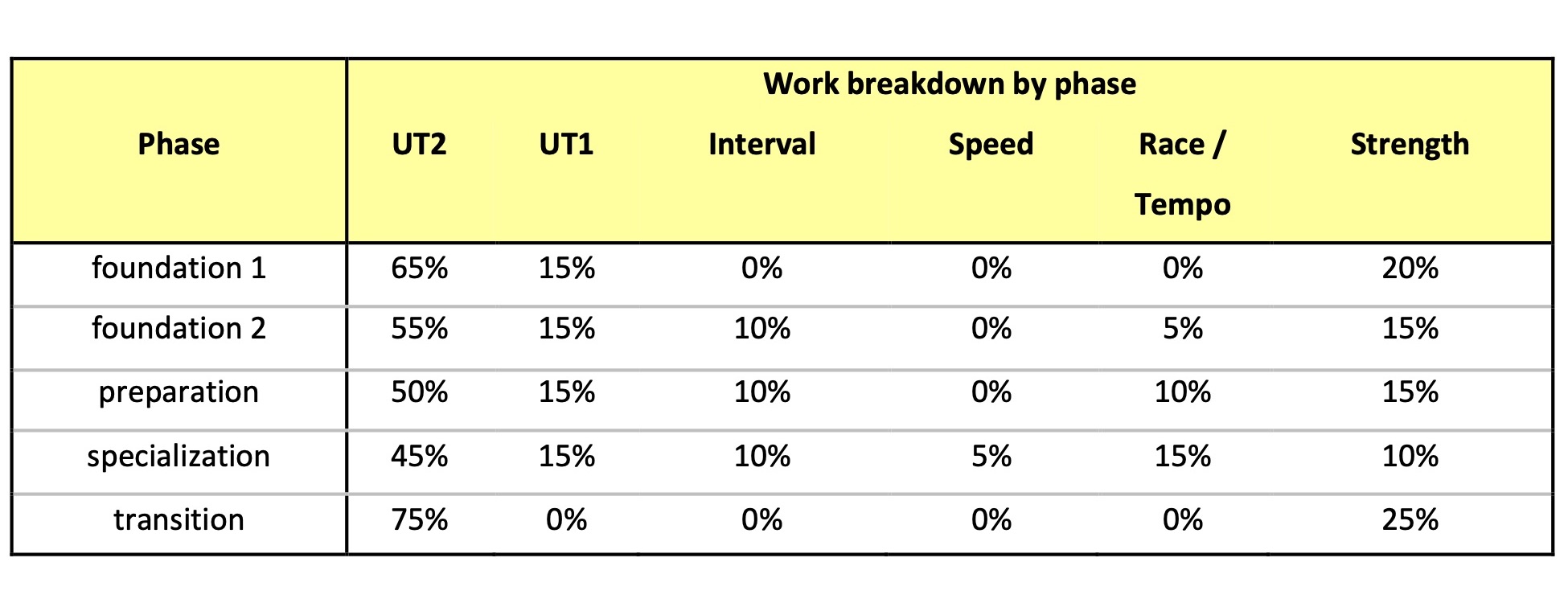

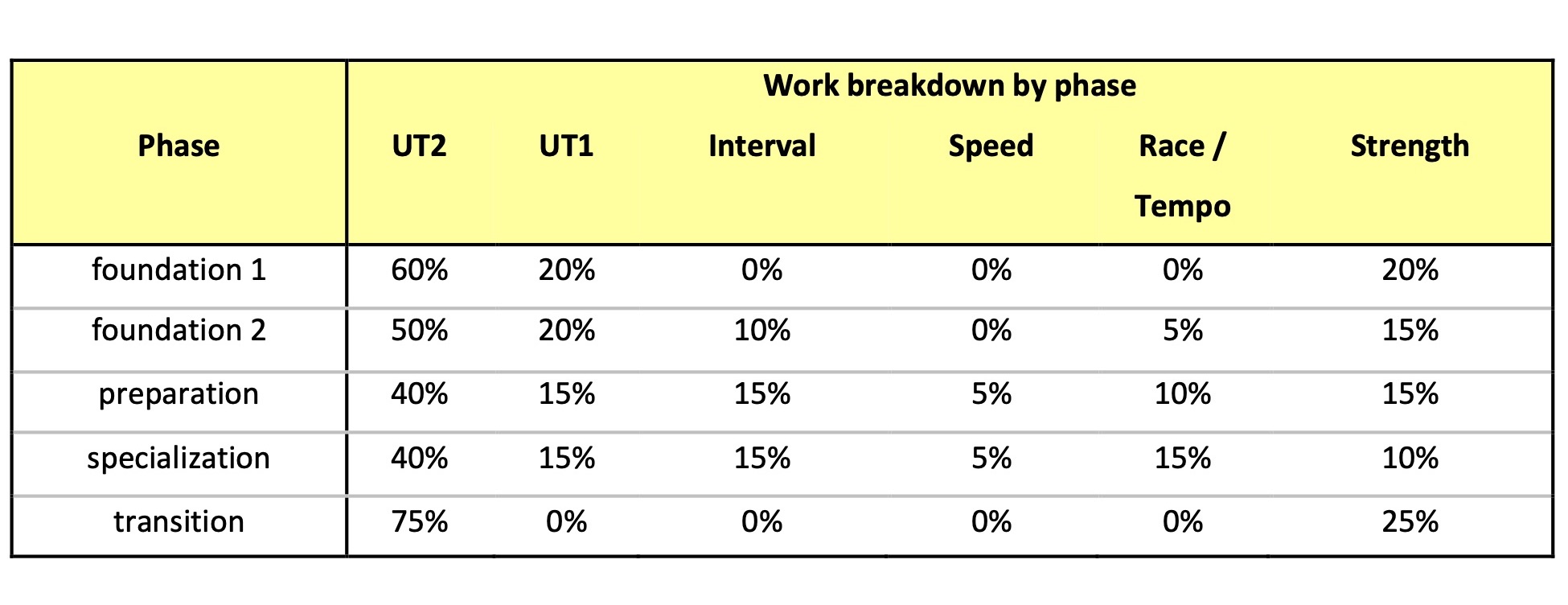

Example work breakdown percentages by training phase for recreational paddlers/racers, marathon paddlers, and sprint distance paddlers are presented in Tables 7 through 9. Work breakdown only changes between phases. This makes intuitive sense, since the goal of each phase is to develop certain types of functional fitness. The work breakdown within a cycle can be adapted to facilitate tapering, or address overtraining (by eliminating anaerobic work, reducing training volume, and/or spending more time cross training). However, except for these specific training needs, changing the work breakdown cycle-to-cycle (or worse, week-to-week) just introduces needless complexity into your training plan.

Table 7: Work breakdown for a recreational paddler or racer.

–

Table 8: Work breakdown for a marathon paddler.

–

Table 9: Work breakdown for a sprint-distance paddler.

–

The work breakdown for each category of paddler can be adapted to meet more specialized training needs – anaerobic endurance, speed, etc. – by slightly tweaking the percentages; just make sure they add up to 100% across each phase. Or, your racing goals may change during a season: you began the year preparing for a long-distance event, but now want to target shorter-distance races. Adapt away; just be sure that the work breakdown makes sense metabolically and is consistent with your goals. With time and experience you’ll know how to adapt these structures on the fly as your schedule and conditions change.

Since work breakdown by training type applies across an entire training phase, it applies to all cycles within that phase, and consequently to all weeks within that phase as well. We’ve learned how to divide the training season into phases, and how to allocate week-to-week variations in training volume within each training cycle. All we need to do now is apply the work breakdown to your training weeks, and voila! You’ll have your workout hours proportionately allocated by the various types of training for every week of your program. This is the outline of your training plan. Examples for 4- and 3-week training cycles appear in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Example work breakdown by week for 4- and 3-week cycles.

The Training Week

While we now know what mix of workouts to include in a given week, we still need to know what workout to do on Monday, Tuesday, and every other day of the week. Despite our quantitative understanding of paddling’s physiological and metabolic systems, there is still some art in the process of planning your week. Here are a few guidelines for planning the training week:

- There are certain scheduling “anchors” within each week. For example, most paddlers perform their long over-distance workouts on the weekend. Races are usually scheduled on weekends as well. You may have a regular weekly group paddle or time trial. These draw down the hours allocated to each week by your planning. Schedule the anchors first; fit the balance of your workouts around these.

- Incorporate at least one rest day per week into your training schedule to aid in recovery. Two rest days per week during racing season are even better – you need to be fresh and on top of your game to race well.

- In general, alternate hard and easy training days so that your body has time to recover and consolidate gains from intervals, racing, and speed workouts. Easy or “recovery” paddling workouts done at less than 60% Karvonen intensity will help build and/or maintain your aerobic base; these aren’t “junk miles” since training is defined as the combination of both work and rest. The work elements are designed to overload the metabolic and muscular systems of the body. By adopting the “hard/easy” training principal and incorporating recovery days these systems rebuild themselves stronger than before.

- Experienced marathon paddlers benefit from so-called “sandwich” workouts, where they schedule long over-distance workouts on consecutive days. The body isn’t fully recovered for the second workout, simulating the fatigue one encounters in long races. This might entail a 3 to 4-hour paddle on a Saturday followed by a 4 to 5-hour paddle on Sunday.

- If sandwich workouts don’t fit your schedule marathon paddlers might consider adding at least one longer workout during the week in addition to their over-distance paddle on the weekend.

- You can add volume to your training week by adding over-distance miles at the end of an interval or tempo workout. Putting in a 30- to 60-minute aerobic paddle immediately after a hard interval session is most definitely a way to get used to the fatigue experienced in long races.

- Break up your long workouts as needed to accommodate your schedule. Scientific studies show that there is no benefit or cost to multiple training sessions per day as opposed to single daily workouts. Multiple training sessions are more a matter of convenience, so feel free to divide your training into morning and evening sessions if needed. If you are combining skills work with endurance training on a single day, perform the skills session first so that you’re sharp. Be sure to give your body sufficient time to replenish glycogen stores between consecutive hard workouts, either on the same day or between an evening workout and a morning workout the next day.

We’ll next provide examples of how you might lay out training weeks to satisfy these guidelines and constraints for the four major phases of the training year.

Foundation Phase

Training weeks within the foundation phase have lower volume and emphasize aerobic capacity development. The shortest workouts should at least 30 minutes in length. In order to promote the metabolic adaptations from aerobic training – increased mitochondrial density, enhanced fat metabolism, improved enzymatic efficiency – you should schedule at least one long over-distance training session every two weeks; ideally, one per week. Strength training days can be alternated with aerobic training days.

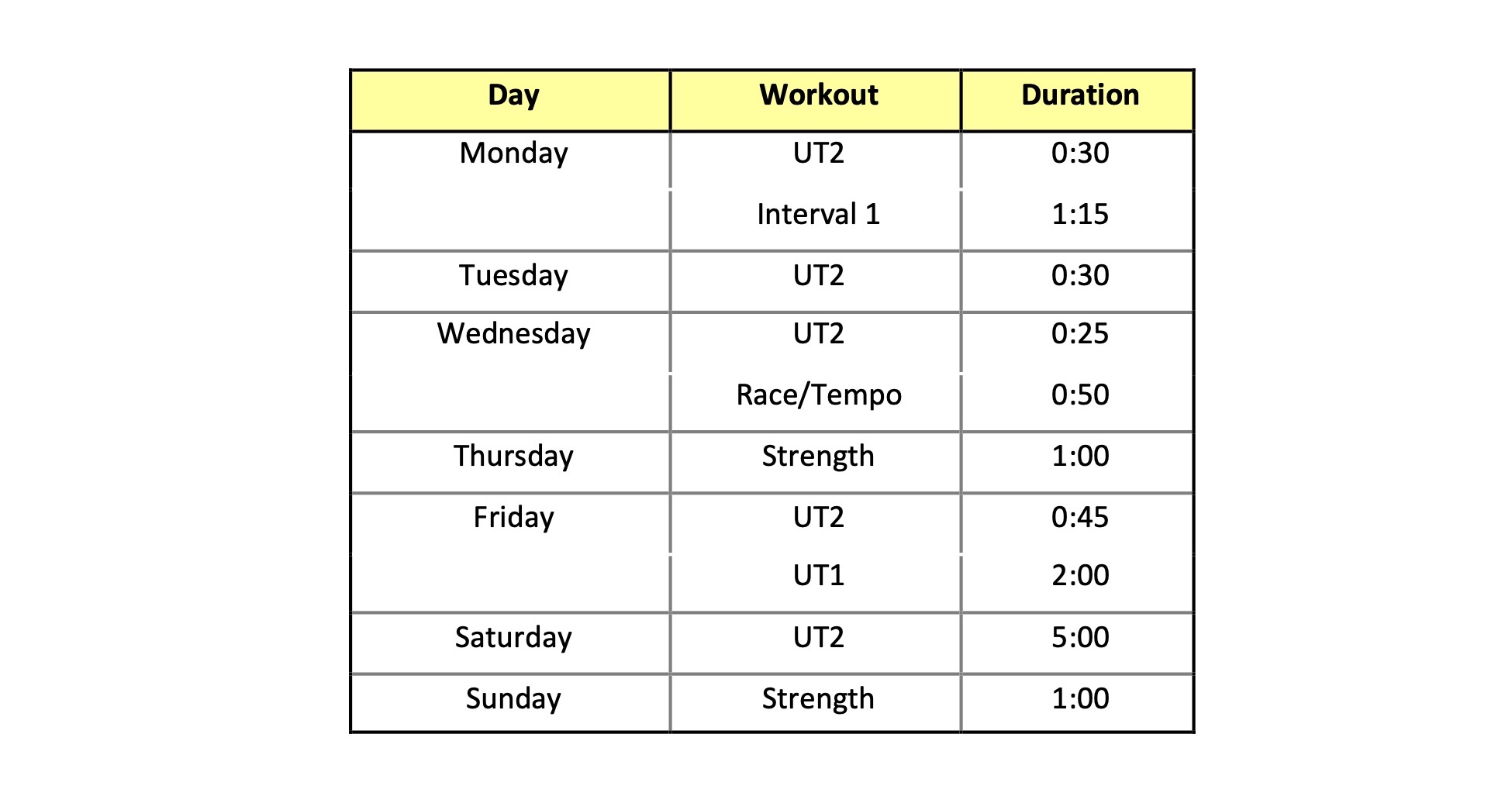

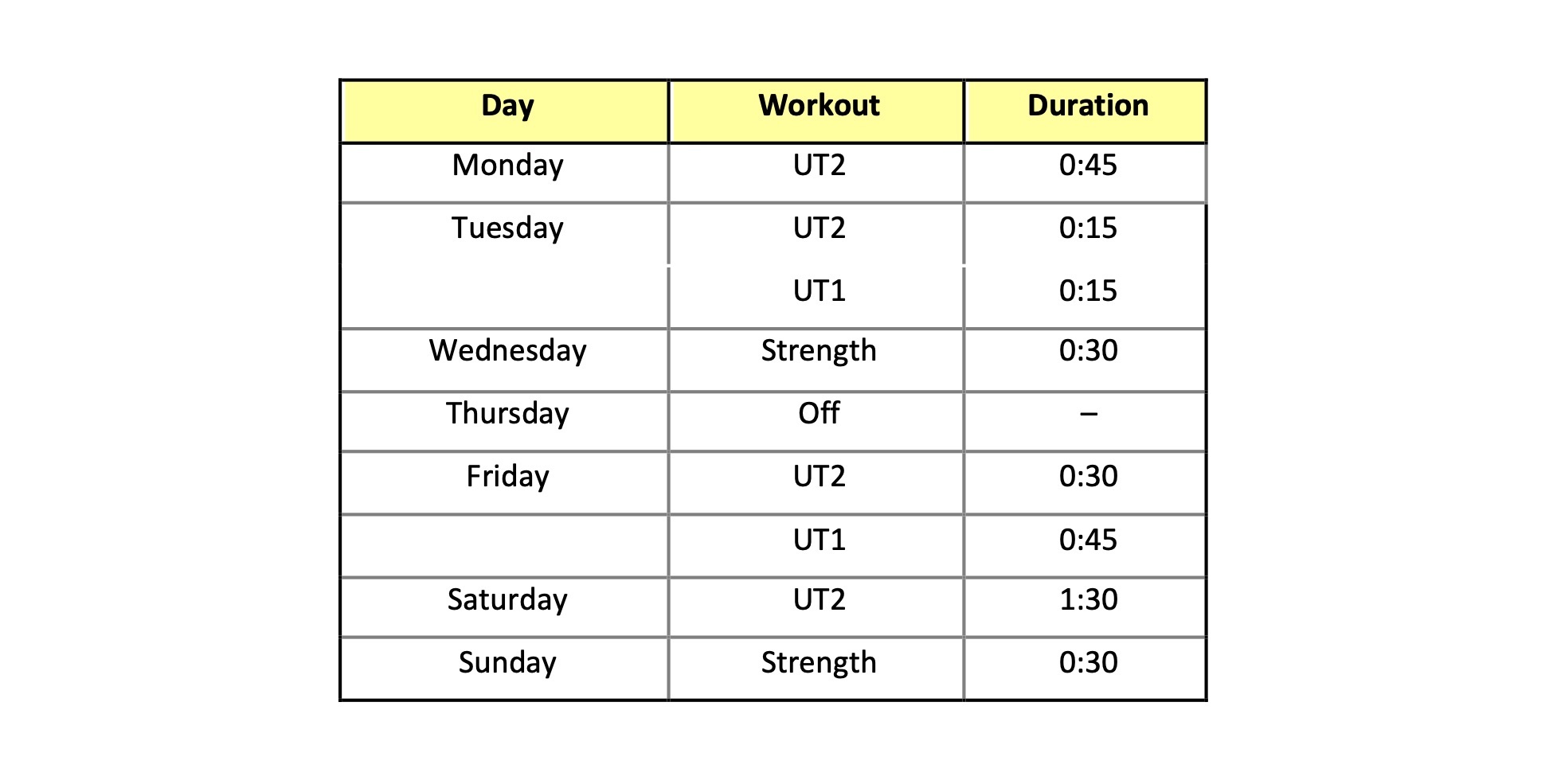

Example training weeks for recreational paddlers/racers and marathon paddlers are presented in Tables 10 and 11, respectively. You can move days around for your scheduling convenience; some paddlers prefer to have their day off on Monday, others on Sunday, while others might prefer to schedule their long workouts on Sunday, etc. Just try to follow the hard/easy principle, and include at least one full rest day per week.

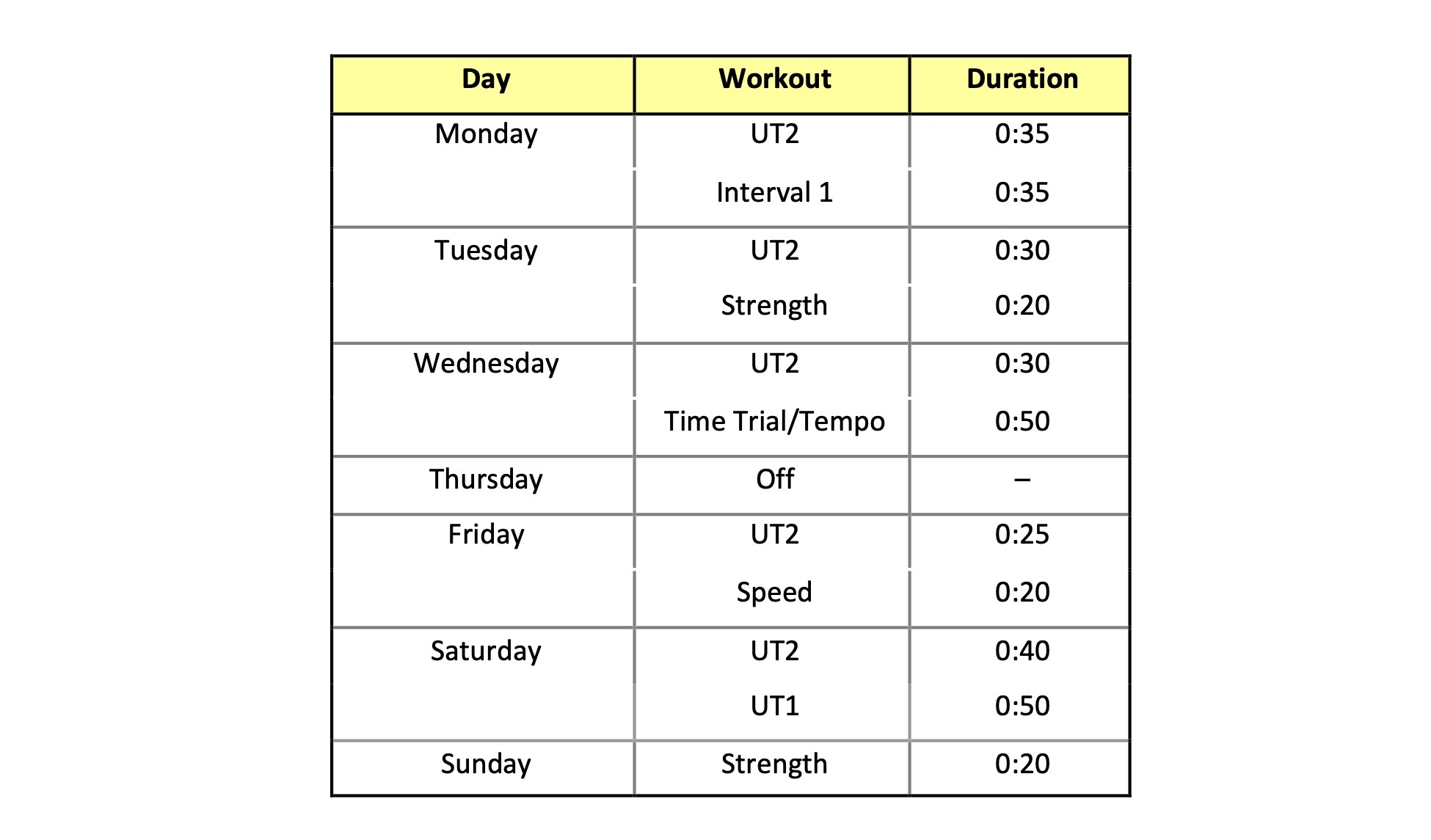

Table 10: Sample breakout of 5:00 week, foundation phase, recreational paddler.

–

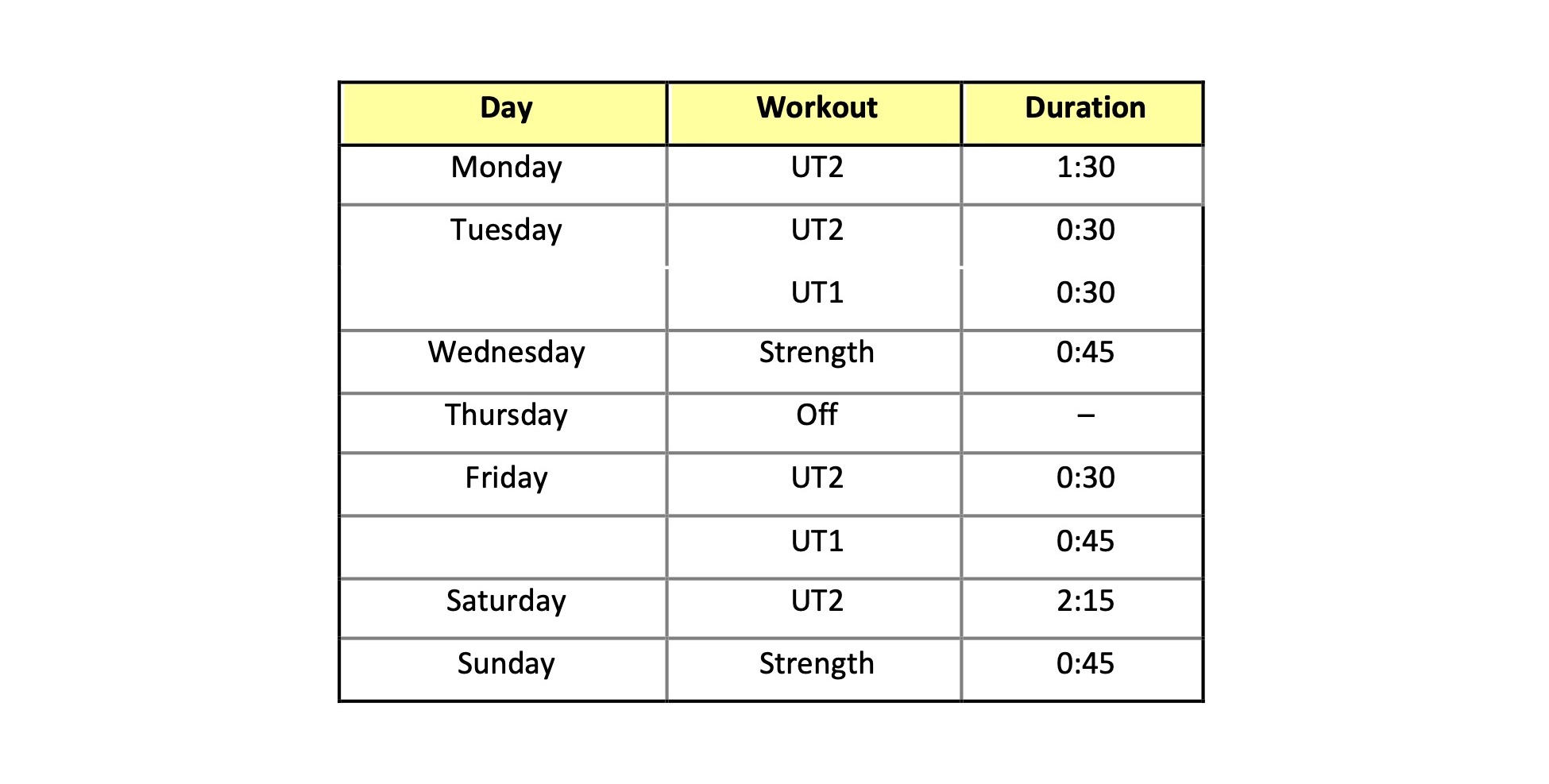

Table 11: Sample breakout of 7:30 week, first half of foundation phase, marathon paddler.

–

The weekly program changes slightly during the second half of the foundation phase (“foundation 2”) for marathon paddlers, especially those targeting long-distance events; see Table 12 for an example. Long-distance paddlers will find it beneficial to schedule long aerobic sandwich workouts on consecutive days. Long aerobic paddles stress the body’s recovery mechanisms. Scheduling two long aerobic workouts on consecutive days heavily stresses these recovery mechanisms. Over time, sandwich workouts help the body prepare for ultra-distance events. They also train the paddler to manage the stress of incomplete recovery: the second workout will feel similar to the latter stages of a long-distance race. Yes, sandwich workouts violate the hard/easy principle. But as long as you experience proper recovery (in terms of rest heart rate, sleep patterns, aerobic threshold pace, etc.) they really benefit the long-distance paddler. And sandwich workouts preclude extraordinarily long workouts on your long over-distance day, e.g. workouts longer than about 6 hours.

Table 12: Sample breakout of 9:30 week, second half of foundation phase, marathon paddler.

–

If you choose to perform sandwich workouts, allocate more UT1 (upper aerobic) volume to the first day, especially if this day is the shorter of the two. That way the perceived difficulty of these consecutive workouts will be approximately equal. Keep your body fueled and hydrated during these workouts. And be sure to load up on carbs to restore muscle glycogen between workouts, or you’ll bonk (harder) on the second day.

The second half of the foundation phase for marathon paddlers also introduces interval training for the first time. Consider starting interval training with long intensive intervals, e.g., Interval 2 sessions. Interval 2 work is done at 85% HRmax; the goals are to lay the groundwork for anaerobic metabolic training, and to develop or reinforce motor engrams for faster paddling (in other words having more than one gear).

Feel free to integrate cross training into your foundation phase weeks. Try to bound cross training to less than 15% of your total weekly mileage if you can. Also, quality work shouldn’t be performed as cross training if at all possible; quality should go hand-in-hand with specificity. For example, in Table 12 the Tuesday UT2 (lower aerobic) session could be a trail or treadmill run; this serves to offload the paddling muscles from Monday’s interval session. But don’t substitute track work for Monday’s intervals. Quality work is intended to provide paddling-specific metabolic (in this case, anaerobic) and neuromuscular benefits.

Preparation Phase

The preparation phase builds on the latter half of the foundation phase, with continued increases in volume and intensity. Recreational paddlers will incorporate a modest amount of Interval 2 work into their weeks. For marathon and sprint paddlers quality training now migrates to short intensive intervals, e.g., “Interval 1” sessions, done at 90-95% HRmax.

The marathon racer can consider incorporating tempo sessions into the training week. Tempo training is paddling done at the same pace as your goal race, but over a shorter distance. The pace may be upper aerobic (UT1) or anaerobic depending on your targeted event; tempo sessions familiarize you with race pace. Choose from tempo paddles, local races, and time trials for a second quality workout each week. Schedule only two quality sessions per week during this high-volume phase to ensure adequate recovery. A sample preparation phase training week for marathon paddlers is presented in Table 13. Short race paddlers (“sprint” for lack of a better term) may wish to incorporate a weekly speed training session toward the end of the specialization phase, especially if they plan to taper training volume.

Table 13: Sample breakout of 13:00 week, preparation phase, marathon paddler.

–

Tapering

As the preparation phase winds down you will likely taper training in anticipation of your race season or goal event. Tapering is the process of reducing training intensity and/or volume in preparation for a race. Tapering is not the same as detraining, which comes from the complete cessation of workouts for an extended period of time. Research has shown that muscle strength actually increases during a properly designed taper, with no reduction in VO2max or aerobic endurance. Think of tapering as distributing recovery over time, which permits your body to recharge before a race. The number of workouts per week does not decrease significantly during the taper, but the duration of each session does. It is easier to recover from several short workouts than it is to recover from a few long workouts.

There are two types of tapers: major tapers prior to important “goal” races, and minor tapers prior to lesser or local races. The duration of the taper depends on the length of the race and the number of hours you typically train per week; the specifics are more art than science. During the taper reduce your training volume as follows:

- For a three-week major taper, such as you might employ before a marathon or ultra, reduce training volume each week by 30% of the previous week’s volume.

- For a two-week major taper reduce training volume each week by 45% of the previous week’s volume.

- For a one-week taper reduce training volume by 50-70%.

In each case, schedule the least amount of work on the days nearest the race, and take a complete rest day the day before the event. If you get twitchy, which is the sure sign you’re ready to race, try some gentle yoga or stretching, or take a walk. Eliminate anaerobic and strength training over the 4 to 7 days immediately prior to the race. Give your body 3 to 4 days to top off glycogen stores for any major race lasting longer than 60-90 minutes.

So-called minor tapers are used prior anaerobic threshold tests or local races. If your training volume is low, just take a day off. If your training volume is moderate use a three-day taper: those with high training volumes might consider a 5-day taper.

Tapering is especially important during the specialization phase, which we will discuss next.

Specialization Phase

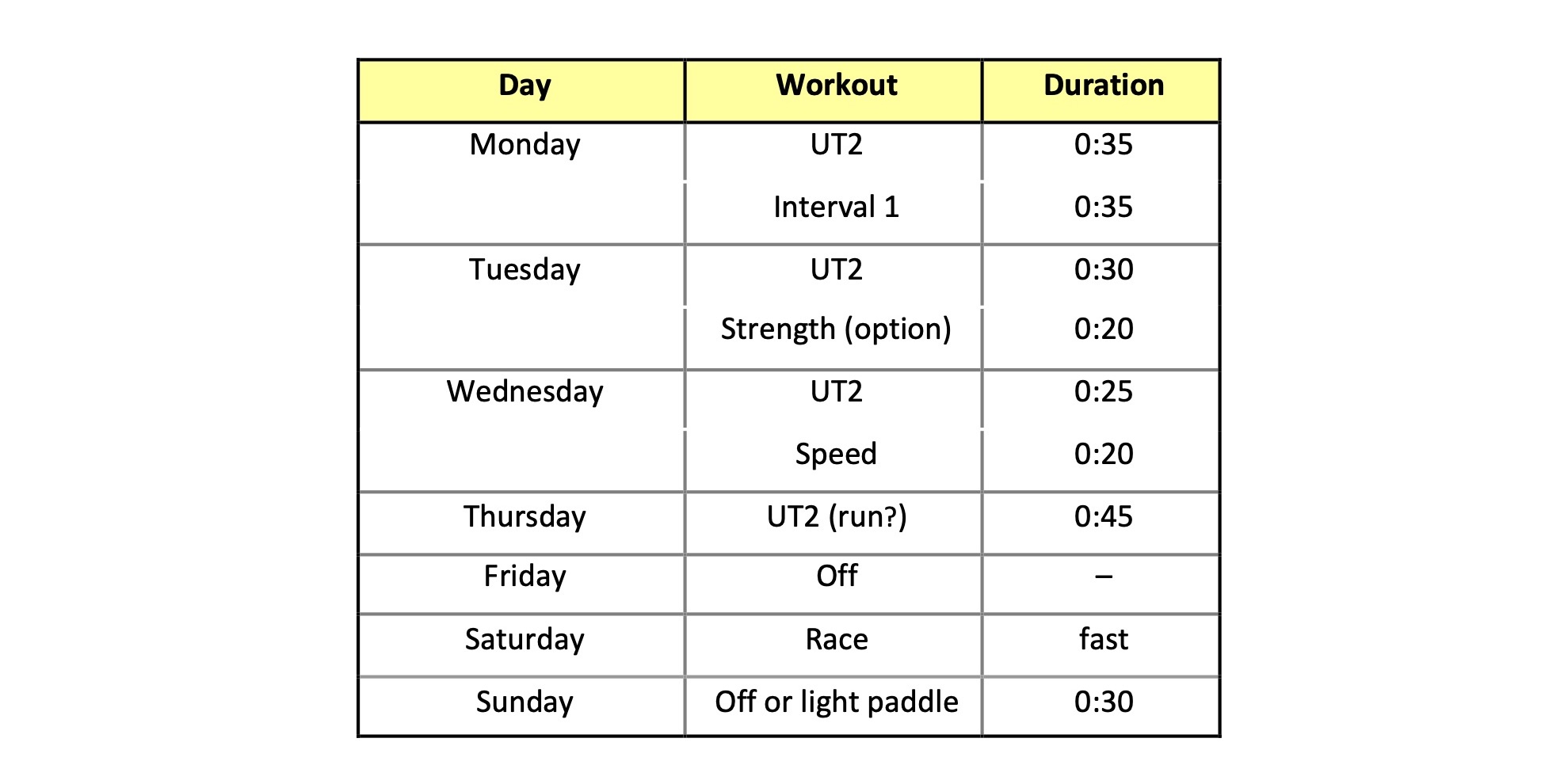

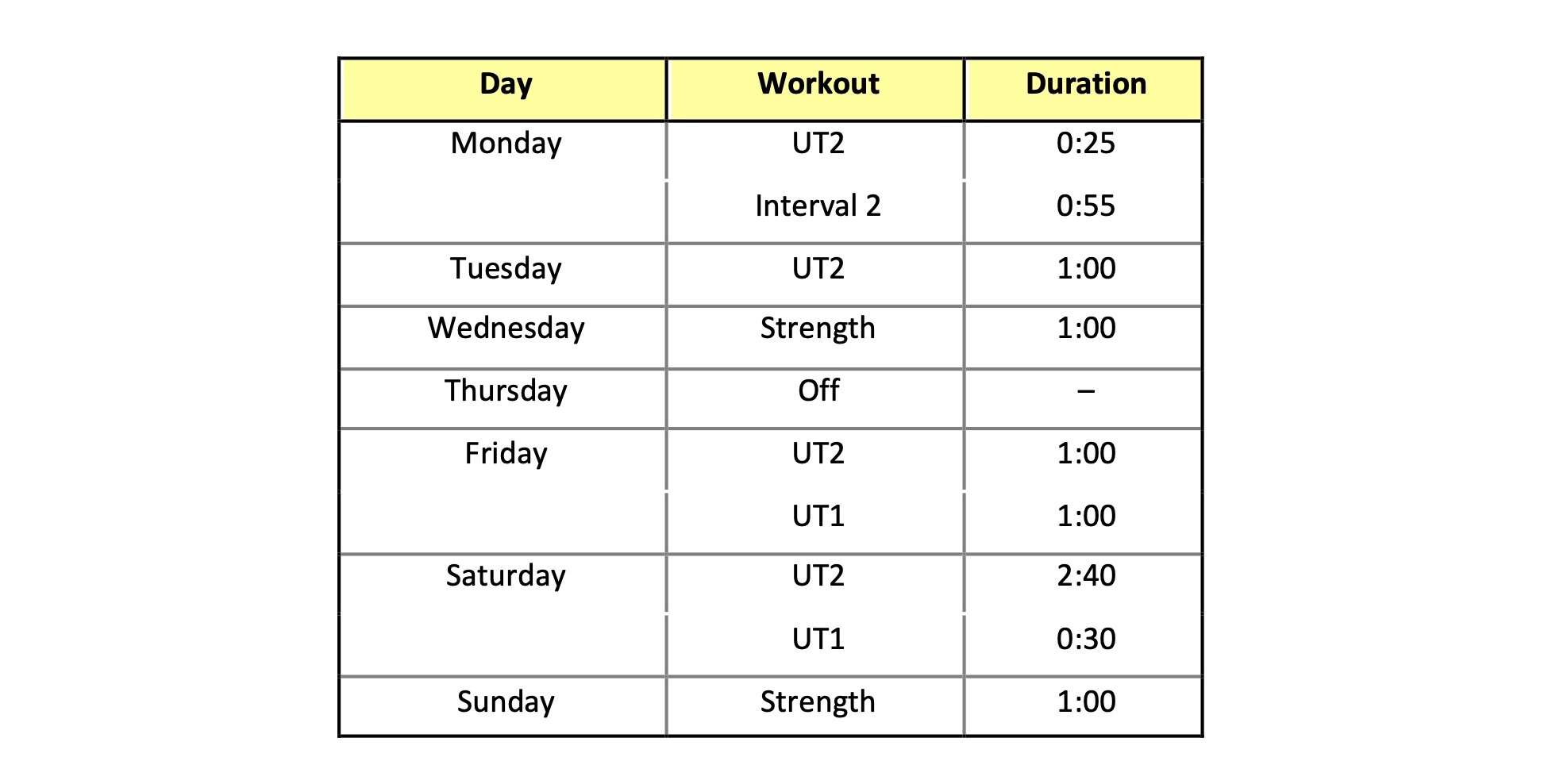

During the specialization phase training volume decreases, and the proportion of quality work increases. A sample non-racing week for a marathon paddler is shown in Table 14.

Intervals during the specialization phase should be done at the high end of Interval 1 intensity, with an extensive warm up (20 minutes) and cool down (15 minutes). Speed training begins in this phase for marathoners. Strength training moves to short maintenance sessions that emphasize power or muscle endurance depending on your race season goals and needs. In essence, the post-interval day paddle, as well as strength training days, are recovery days. On non-racing weeks try to include one long paddle per week to maintain your aerobic base. Strength training sessions can be combined with short UT2 training paddling workouts.

Races generally fall on weekends. On race weeks pass on anaerobic training sessions, or confine them to early in the week; keep them short and sharp. Obviously, you can forego long over-distance training days on race weeks. If you continue strength training, give yourself at least two days recovery before the event. Taper your training volume as described above; an example week’s schedule is presented in Table 15.

Table 14: Sample breakout of 5:30 week, specialization phase, marathon paddler.

–

Table 15: Sample breakout of tapering week, specialization phase, marathon paddler.

–

Transition Phase

You’ve worked hard during the year, building your training volume in the foundation and preparation phases. And you’ve had fun racing during the specialization phase, hopefully realizing many of the goals you set for yourself prior to training. Now, your body could stand a rest; a break from all that paddling. It’s time for the off-season, otherwise known as the transition phase.

During the transition phase try to spend most of your time cross-training. Consider hanging up the paddle for a while to give your paddling muscles a break. The transition phase is a great time for mountain biking or trail running, swimming, or taking a yoga class (if you haven’t been doing all along). The training volume in this phase is light. Your goal is to maintain aerobic fitness, not build it. As to weight training, work on exercises that address deficiencies you’ve observed over the year, perhaps emphasizing single-handed lifts to build or reinforce side-to-side symmetry. Schedule two off days per week; you’ll find a sample transition phase week for all paddlers in Table 16. Work on enhancing your flexibility and general fitness; it’s a great opportunity to try tai chi or yoga.

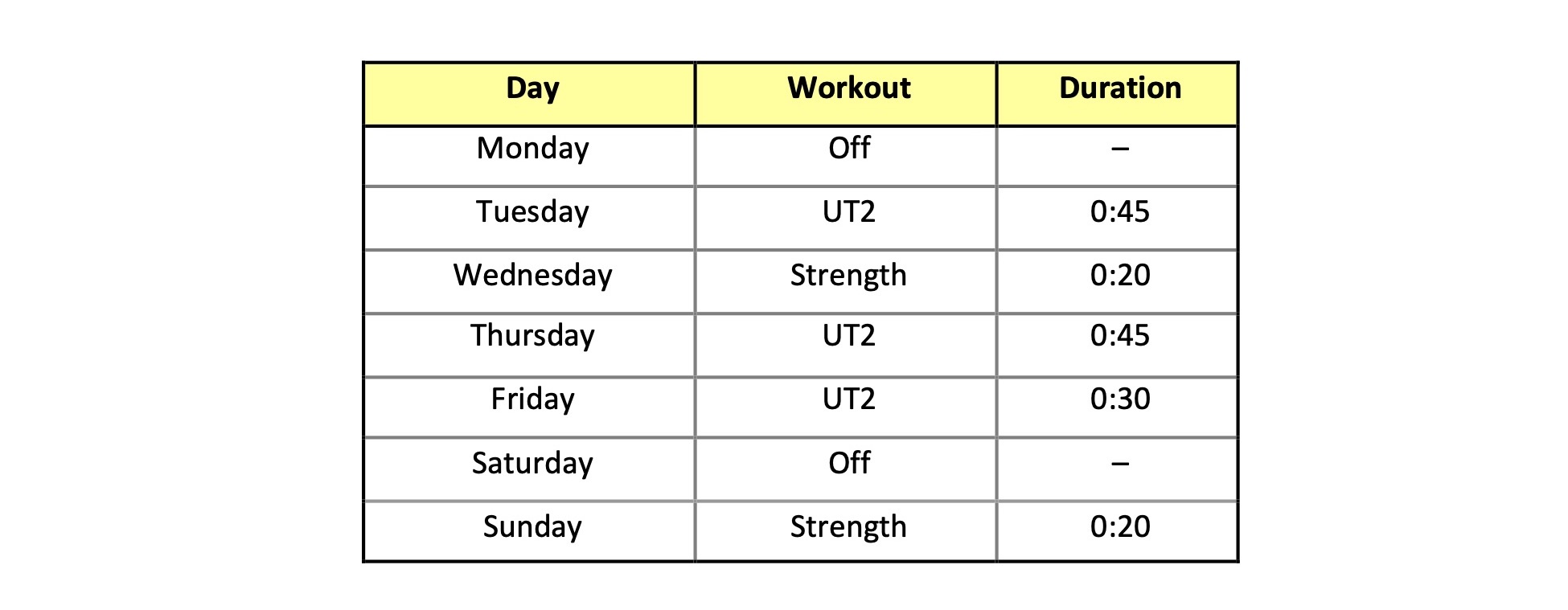

Table 16: Sample breakout of 3:00 week, transition phase.

–

There – you’ve done it! You’ve gone from goal setting through the various phases of top-down planning for the training year. With the concepts laid out above, you too can develop your own detailed, personalized training program. Change it on the fly while still honoring your training goals. And know why you’re doing each and every workout.

INTEGRATING STRENGTH TRAINING

The work breakdown for the overall training plan allocates time for strength training. Strength training can be successfully integrated into the overall program once you have designed a strength program that meets your needs. We’ll consider a few examples in this section following the models presented by Tudor Bompa.

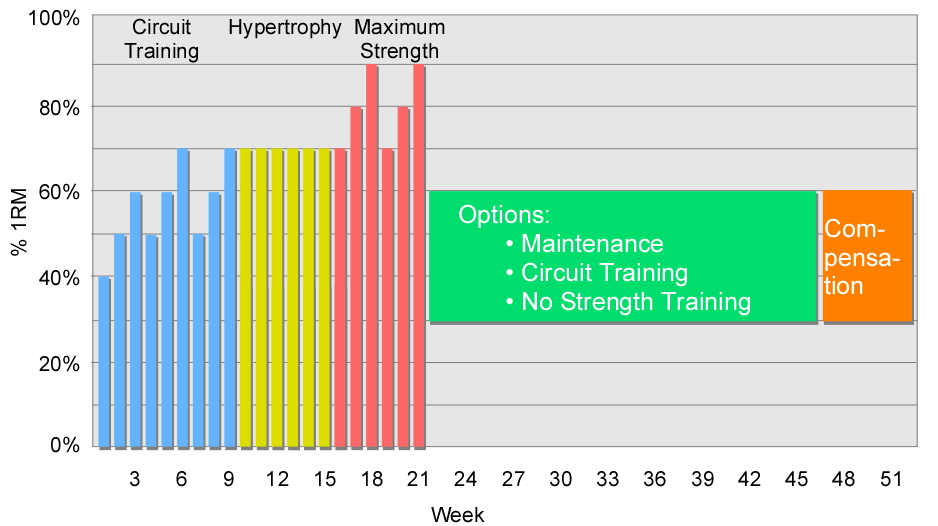

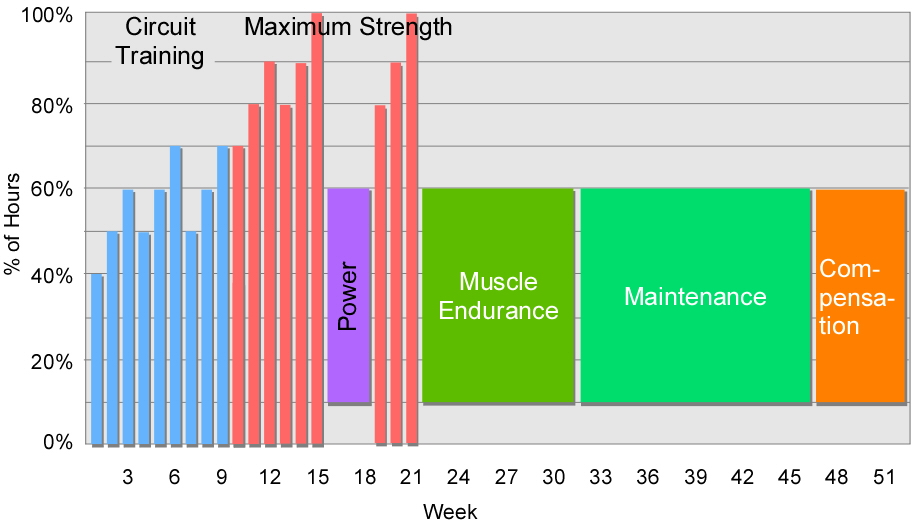

A candidate lifting program for a recreational paddler/racer that is new to strength training appears in Figure 10. The program begins with 9 weeks of circuit training. The circuit training phase is composed of three 3-week cycles, targeting weights as shown in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Annual lifting program for recreational paddler/racer.

Circuit training prepares the muscles, bones, and tendons for later lifting phases. The circuit training phase is followed by a 6-week hypertrophy phase. Hypertrophy is an increase in muscle mass brought about by lifts done at 70-75% of 1RM. Exercises in this phase should focus on the prime movers and major muscle groups, and de-emphasize dumbbell work. The increased muscle mass developed in this phase will further prepare a strength training newbie for the ensuing maximum strength training phase indicated in the figure. Maximum strength is trained for 6 weeks, in two 3-week cycles, and does not employ maximal (100% 1RM) lifts in any week.

Following this extensive preparation, the rec paddler will have to decide whether they wish to continue integrating strength training into their overall training program. New racers will benefit from strength maintenance during the specialization phase focusing on muscle endurance, which entails high-rep functional exercises done at low (~50% 1RM). Recreational paddlers can continue circuit training. Or, if time is at a premium, recreational paddlers and racers can focus their time on the water, and dispense with strength training altogether. The final weeks of the training year, during the transition phase, all paddlers will be benefit from two short compensation lifting sessions per week.

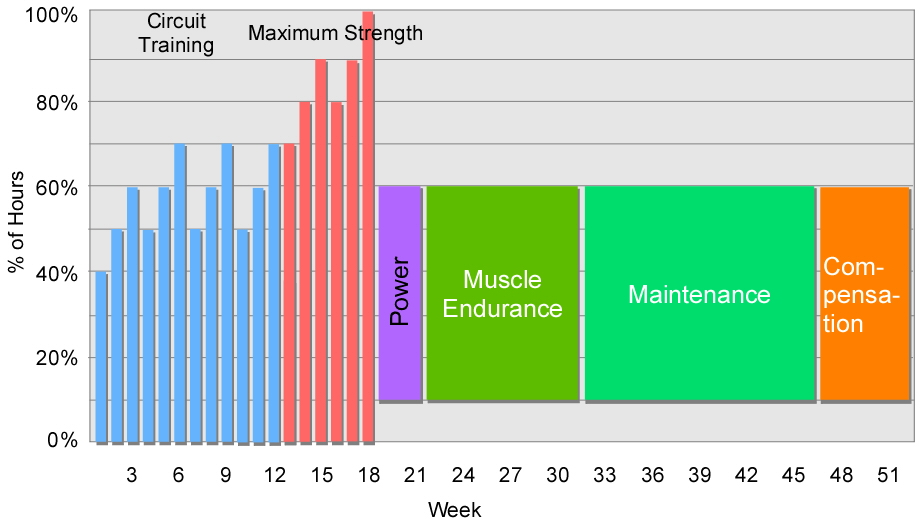

A sample lifting program for a marathon racer appears in Fig. 11. The program begins with 12 weeks of circuit training. The circuit training phase consists of four 3-week cycles, targeting weights as shown in the Figure. This is followed by a 6-week maximum strength training phase. The second 3-week cycle of maximum strength workouts employs maximum (100% 1RM) lifts, which should only be performed by paddlers with a few years of strength training under their belts; less experienced strength trainers should perform a second 70%-80%-90% cycle. This is followed by a 3-week power training phase to maximize muscle synchronization. The power phase is followed by a 9-week muscle endurance training phase. Paddlers targeting shorter distances might forego a portion of muscle endurance training, and double the length of the power training phase. Either way, this is followed by maintenance lifting during the specialization training phase. Maintenance should be a mix of power and muscle endurance maintenance exercises, as well as periodically revisiting power training to ensure that quality hasn’t diminished.

Figure 11: Sample annual lifting program for marathon racer.

A variation on this lifting program appears in Fig. 12 for those paddlers who have been strength training for a number of years. The program begins with 9 weeks of circuit training. The circuit training phase is followed by a 6-week maximum strength training phase, where the second 3-week cycle employs maximum (100% 1RM) lifts. This is followed by a 3-week power training phase to maximize muscle fiber synchronization. In order to consolidate gains made in fiber synchronization, the power training phase is followed by a second 3-week maximum strength phase. Paddlers following this program will find that their 1RM lifts have increased over the previous 9 weeks of work, yielding a greater strength reserve. This is followed by a 9-week muscle endurance training phase. Since 1RM will have increased, the muscle endurance phase will be challenging: a greater 1RM means heavier weights for long muscle endurance workouts. Muscle endurance training is followed by maintenance work during the specialization training phase. As before, maintenance should be a mix of power and muscle endurance strength training.

Figure 12: Sample annual lifting program for marathon racer.

As you can see, there are a number of ways you can mix and match strength training program elements depending on your particular needs and goals. The strength programs described above are merely illustrative examples.

We’ve noted that several of the strength training phases utilize 3-week cycles. Consequently, if you’re aerobic/anaerobic training uses a 4-week cycle, you can be out of phase with your strength training cycles much of the time. The best way to align them is to reduce strength training volume during on-water recovery weeks, e.g. do fewer strength training sets during lower-volume weeks.

Paddlers with annual training volumes under 200 hours may find that the work breakdown of training hours devoted to strength training is small. Use this work breakdown with a grain of salt; just limit your sets during the circuit training phase, and for the maximum strength and power phases if strength isn’t one of your training priorities. Emphasize quality over quantity.

MISCELLANEOUS

Warming Up and Cooling Down

When we start to train or race, oxygenated blood and nutrients are channeled to the working muscles to fuel your efforts. At rest, half or more of your blood volume is devoted to your internal organs. When you train or race, a significant portion of this blood is diverted to your muscles. During anaerobic workouts and races as much as 80% of your blood flow can be directed to the working muscles. The sudden shift in blood flow at the beginning of a training session or race can be a significant shock to the body. One way to prevent this is to incorporate an extensive warm up into your workouts.

Warming up prepares the body for training. It generally does not include stretching; this can be done as appropriate at the end of the workout when your muscles and joints are loose and more receptive. Nonetheless your warm-up can include some flexibility and range of motion exercises to help prepare your joints for exercise, in particular your elbows, shoulders, back, and hips. A simple rule of thumb is to warm up for a minimum of 10-15 minutes with light paddling; up to 20 minutes before hard interval sessions or races. Using a heart rate monitor you’ll find that with improving fitness it will take your heart longer to reach each day’s target training zone. Listen to your body, and take more time to warm up.

At the end of your workout, cool down with approximately 10 minutes of easy paddling or jogging. After a hard race, consider cooling down for 10-20 minutes of light paddling and walking. Watch your heart rate drop, and note whether it drops quickly or slowly. This can be a rough indicator of recovery time. The cool down begins the process of recovery, and immediately aids in blood lactate and hydrogen ion removal. Time spent warming up and cooling down should be considered part of that day’s workout; count it as additional over-distance time.

Cross Training

For general fitness and overall athletic balance it is beneficial to cross train a bit in sports that are less focused on the muscles of your back, trunk, and arms, such as running or cycling. Running is especially relevant for those who enter races with portages; the 1.25-mile carry in the Adirondack Classic certainly comes to mind. Cross training allows you to increase total workout volume without risking paddling overuse injuries. But perhaps the chief benefit of cross training is relief from hours of tedium in the canoe or on the paddling ergometer. In fact, if you train indoors during the foundation phase you should consider structuring long workouts so that you switch between a paddling ergometer and a treadmill or elliptical trainer, primarily to combat boredom.

The downside to cross training is specificity. In order to paddle faster, you should paddle, and activities such as running or cycling don’t engage the paddling muscles and their neural pathways. One off-season option in Northern climes is Nordic skiing, which has similar muscle engagement patterns to paddling; many excellent paddlesport racers ski competitively in the winter. And during the season roller skiing or roller blading with ski poles offers many of the same benefits; even hiking with poles helps a bit.

Another downside to cross training is that your heart rate ranges and thresholds will differ from those in the boat. This is due to variations in muscle engagement between sports, and your degree of aerobic and anaerobic adaptation in each sport as well.

Caveats aside, it is still advisable to spend some of your training time in activities other than canoeing. When planning your training program consider devoting 10-15% of your aerobic training volume to a second, complementary sport such as running. Better yet, try trail running, which mimics the terrain you’ll likely encounter on portages, and helps develop balance as you jump rocks and downed trees. During the preparation phase combine over-distance paddling sessions with portage practice. Running with a boat is a learned skill, and you will benefit from practicing the transitions in and out of the boat. Plus it freaks out anyone nearby, which is always a lot of fun. Save the anaerobic training sessions for the boat, as these are intended to develop paddling-specific speed and neuromuscular adaptations.

Using and Modifying Your Training Plan

When developing your plan, you can lay out each week a day in advance, a week in advance, or you may choose to lay out all of your weeks before the training year begins. It’s up to you. Whatever way you choose to plan, it is worthwhile to review each week a day or two before it starts. That way, if your schedule changes you can modify the plan and still maintain training emphasis.

If you have to shorten your training in a given week, try to keep days “of emphasis” on your calendar. For example, if your two primary goals in a training year season or phase are to develop anaerobic threshold and maximum strength, do your best to keep those workouts on your weekly schedule. If your two primary training goals are different, use those two goals to prioritize your week’s training. No matter what, use the hard/easy principle when rescheduling your week.

If you miss some training volume in a week, don’t try to make it up all on one day, or tack on additional time in a succeeding week. If you do you run the risk of overloading your capacity to recover. Instead, just resume your existing plan where you left off, or modify it to maintain training emphasis as described above. If, however, you miss a significant amount of training in a week, consider ramping down the following week’s volume and/or intensity using the 10% rule. If you missed significant training volume due to illness, you should both reduce volume and especially reduce or even eliminate quality work in the succeeding week. Either way, you’ll catch up with your annual training plan during the next down week within your training cycle.

Your training plan is just that: A plan. There will be a difference between your plan, and what training actually gets done. As a wise person once said, “Life happens.”

And last but not least, we all have days where we’d rather do anything but train. You have three options. First, you can blow off the day, and resume or modify your training schedule as described above. Try not to do this very often, or you won’t be training any more; you’ll merely be working out. Other antidotes for the blahs include cross training – time away from the boat or the erg might do you good – or exchanging a quality workout for an over-distance session. Sometimes a change like that will see you through a low energy swing. If you decide to try your scheduled workout anyway, work out for at least 15 minutes. Sometimes that amount of exercise will help you find your mojo: a few of the author’s best workouts have come about this way. If, however, none of these approaches work, call it a day, and muster your energy for tomorrow.

Record Keeping

Good record keeping is a must to track your training program. By reviewing your training log you can marvel at your progress, and look for trends, either positive or negative, which allow you to tune your training to your evolving needs. Once you set up your training log it takes just a couple of minutes per day to update the log with each workout, plus your previous night’s hours of sleep and your morning rest heart rate and weight. Be sure to include qualitative information such as how you felt during the workout, weather and water conditions, any aches or pains, technical issues or breakthroughs, food eaten through the day, etc. As the year progresses, and certainly at the end of the year, read through your log. It will help you see the big picture regarding trends and progress.

REFERENCES

Aschwanden, Christie, Good to Go: What the Athlete in All of Us Can Learn from the Strange Science of Recovery, W. W. Norton & Company (2019).

Bishop, D., Bonetti, D., & Dawson, B., “The effect of three different warm-up intensities on kayak ergometer performance.,” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, Volume 33, pp. 1026-1032.

Bompa, Tudor, Periodization Training for Sports, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL (1999).

Bompa, Tudor, Periodization: Theory and Methodology of Training, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL (1999).

Burke, Edmund, Precision Heart Rate Training, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL (1998).

Collins, M.A., and Snow, T.K., “Are adaptations to combined endurance and strength training affected by sequence of training?” Journal of Sports Science, Volume 11, Number 6, pp. 485-91 (1993).

Edwards, Sally, The Heart Rate Monitor Book, Polar CIC Inc, Port Washington, NY (1993).

Fekete, Michael, “Periodized strength training for spring kayaking/canoeing,” http://www.sprintkayak.com/StrengthTraining.pdf (December 1998).

Friel, Joseph, Faster After 50: How to Race Strong for the Rest of Your Life, VeloPress (2015).

Hagerman, Frederick, “Resistance training and endurance performance,” http://sportsci.org/news/traingain/resistance.html (1997).

Luke Humphrey with Keith & Kevin Hanson, Hansons Marathon Method: Run Your Fastest Marathon the Hansons Way, VeloPress; 2nd edition (2016)

Isaka, T., & Takahashi, K. “Effects of off- and pre-season training on aerobic and anaerobic power of kayak paddlers,” Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, Volume 29, Number 5, Supplement abstract 1242 (1997).

Johnson, Kenneth E., “Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE), http://www.3-fitness.com/tarticles/rpe.htm (2005).

Johnson, Kenneth E. “Training zones,” http://www.3-fitness.com/tarticles/zones.htm (2005).

Maffetone, Philip, Training for Endurance, David Barimore Productions, Stamford NY (1996).

Nolte, Volker, Rowing Faster, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL (2005).

Pfitzinger, Pete, “Tapering for optimal racing performance,” http://www.copacabanarunners.net/i-tapering.html (2004).

Seiler, Stephen, “XC endurance training theory – Norwegian style,” http://home.hia.no/~stephens/xctheory.htm (1997).

Sleamaker, Rob, and Browning, Ray, SERIOUS Training for Endurance Athletes, 2nd Edition, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL (1996).

Snyder, Rocky, Fit to Paddle, Ragged Mountain Press, Camden, Maine (2003).

http://www.nismat.org/physcor/max_o2.html, “NISMAT Exercise Physiology Corner: Maximum Oxygen Consumption Primer” (2005).

Your Guide to Basic Training Principles | TrainingPeaks

Principles of Exercise and Sport Training (teamusa.org)

V1.1

©2020, Shawn Burke and Kevin Olson. All rights reserved. See Terms of Use for more information.

- In fact, any plan that gets you to train works compared to having no plan.. ↑

- * If you are starting from scratch, consider a baseline training volume of 120 to 150 hours per year. ↑

- Peter Janssen, Threshold Training, Human Kinetics, Champaign, IL (2001). ↑

- * Training is sometimes divided into “mesocycles,” “macrocycles,” and “microcycles;” no doubt “nanocycles” are on the way. We’ve adopted the terms “phase” and “cycle” for simplicity. ↑

- Those of you who have toiled over Gantt charts will be familiar with this term. ↑